Difference between revisions of "Enterprise Systems Engineering"

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

===Primary References=== | ===Primary References=== | ||

| + | Bernus, P., Nemes L., and Schmidt G., eds. 2003. ''"[[Handbook on Enterprise Architecture]],"'' Berlin & Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag. | ||

| + | |||

Rebovich, G. and B. E. White, eds. 2011. ''"[[Enterprise Systems Engineering: Advances in the Theory and Practice]]."'' Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Auerbach. | Rebovich, G. and B. E. White, eds. 2011. ''"[[Enterprise Systems Engineering: Advances in the Theory and Practice]]."'' Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Auerbach. | ||

| Line 152: | Line 154: | ||

Rouse, W. B. 2009. "[[Engineering the Enterprise as a System]]." In ''"Handbook of Systems Engineering and Management."'', eds. A. P. Sage, W. B. Rouse. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Wiley and Sons, Inc. | Rouse, W. B. 2009. "[[Engineering the Enterprise as a System]]." In ''"Handbook of Systems Engineering and Management."'', eds. A. P. Sage, W. B. Rouse. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Wiley and Sons, Inc. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Valerdi, R. and Nightingale, D. J. 2011. "[[An Introduction to the Journal of Enterprise Transformation]]," ''Journal of Enterprise Transformation, 1''(1), 1-6, 2011. | Valerdi, R. and Nightingale, D. J. 2011. "[[An Introduction to the Journal of Enterprise Transformation]]," ''Journal of Enterprise Transformation, 1''(1), 1-6, 2011. | ||

Revision as of 19:52, 27 July 2012

Enterprise systems engineering (ESE) is the application of systems engineering principles, concepts, and methods to the planning, design, improvement, and operation of an enterprise.

To download a PDF of all of Part 4 (including this knowledge area), please click here.

Topics

This series of articles will first provide (1) some background on the scope of ESE, imperatives for enterprise transformation, and potential systems engineering (SE) enablers for the enterprise. It will then discuss (2) how to treat the enterprise as a system and how ESE relates to the concepts of system of systems (SoS) and federation of systems (FoS). Next it will describe (3) related business activities and (4) necessary extensions of TSE concepts that enable these business activities. Each of the ESE process activities is discussed (5) in the overall context of the unique circumstances in the operation of a large and complex enterprise. Finally, it will show (6) how ESE can be used to establish and maintain enterprise operational capabilities. The six topics for this knowledge area are listed below.

- Enterprise Systems Engineering Background

- The Enterprise as a System

- Related Business Activities

- Enterprise Systems Engineering Key Concepts

- Enterprise Systems Engineering Process Activities

- Enterprise Capability Management

Introduction

This knowledge area provides an introduction to systems engineering (SE) at the enterprise level in contrast to “traditional” SE (TSE) (sometimes called “conventional” or “classical” SE) performed in a development project or to “product” engineering (often called product development in the SE literature).

The concept of enterprise was instrumental in the great expansion of world trade in the seventeenth century (see note 1) and again during the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The world may be at the cusp of another global revolution enabled by the Information Age and the technologies and cultures of the Internet (see note 2). The discipline of SE now has the unique opportunity of contributing its tools and methods for the next round of enterprise transformations, working with the other professional disciplines involved.

- Note 1. “The Dutch East India Company… was a chartered company established in 1602, when the States-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly to carry out colonial activities in Asia. It was the first multinational corporation in the world and the first company to issue stock. It was also arguably the world's first mega-corporation, possessing quasi-governmental powers, including the ability to wage war, negotiate treaties, coin money, and establish colonies.” (emphasis added, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_India_Company)

- Note 2. This new revolution is being enabled by cheap and easily usable technology, global availability of information and knowledge, and increased mobility and adaptability of human capital. The enterprise level of analysis is only feasible now because organizations can work together to form enterprises in a much more fluid manner.

ESE is an emerging discipline that focuses on frameworks, tools, and problem-solving approaches for dealing with the inherent complexities of the enterprise. Furthermore, ESE addresses more than just solving problems; it also deals with the exploitation of opportunities for better ways to achieve the enterprise goals. A good overall description of ESE is provided by in the book by Rebovich and White (2011).

Key Terms

Enterprise

An enterprise consists of a purposeful combination (e.g., a network) of interdependent resources (e.g., people, processes, organizations, supporting technologies, and funding) that interact with

- each other to coordinate functions, share information, allocate funding, create workflows, and make decisions, etc.; and

- their environment(s) to achieve business and operational goals through a complex web of interactions distributed across geography and time (Rebovich and White 2011, 4-35).

The literature uses the term enterprise in various ways:

(1) One or more organizations sharing a definite mission, goals, and objectives to offer an output such as a product or service. (ISO 15704 2000)

(2) An organization (or cross organizational entity) supporting a defined business scope and mission that includes interdependent resources (people, organizations and technologies) that must coordinate their functions and share information in support of a common mission (or set of related missions). (CIO Council 1999)

(3) The term enterprise can be defined in one of two ways. The first is when the entity being considered is tightly bounded and directed by a single executive function. The second is when organizational boundaries are less well defined and where there may be multiple owners in terms of direction of the resources being employed. The common factor is that both entities exist to achieve specified outcomes. (MOD 2004)

(4) A complex, (adaptive) socio-technical system that comprises interdependent resources of people, processes, information, and technology that must interact with each other and their environment in support of a common mission. (Giachetti 2010)

(5) People, processes and technology interacting with other people, processes and technology, serving some combination of their own objectives, those of their individual organizations and those of the enterprise as a whole. (McCaughin and DeRosa 2006)

An enterprise must perform two separate, but related, functions: (1) develop things within the enterprise to serve as either external offerings or as internal mechanisms to enable achievement of enterprise operations, and (2) transform the enterprise itself so that it can most effectively and efficiently perform its operations and survive in its competitive and constrained environment. The challenges involved in transformation of the enterprise are dealt with by (Rouse 2005) and (Valerdi and Nightingale 2011).

Enterprise Architecture

The principles and concepts of architecture are especially relevant at the enterprise level:

Metaphorically, an enterprise architecture is to an organization's operations and systems as a set of blueprints is to a building. That is, building blueprints provide those who own, construct, and maintain the building with a clear and understandable picture of the building's uses, features, functions, and supporting systems, including relevant building standards. Further, the building blueprints capture the relationships among building components and govern the construction process.

Enterprise architecture does nothing less, providing to people at all organizational levels an explicit, common, and meaningful structural frame of reference that allows an understanding of (1) what the enterprise does; (2) when, where, how, and why it does this; and (3) what it uses to do this. (GAO 2003)

A thorough discussion of enterprise architecture is provided by (Bernus et al. 2003). A description of various architecture frameworks and methodologies is provided in the article called Enterprise Systems Engineering Key Concepts.

Enterprise vs Organization

It is worth noting that an enterprise is not always equivalent to an "organization." An enterprise "can be (1) a single organization or (2) a functional or mission area that transcends more than on organizational boundary (e.g., financial management, homeland security)." (GAO 2003) Giachetti (2010) distinguishes between enterprise and organization by saying that an organization is a view of the enterprise. The organization view defines the structure and relationships of the organizational units, people, and other actors in an enterprise. Using this definition, we would say that all enterprises have some type of organization, whether formal, informal, hierarchical or self-organizing network.

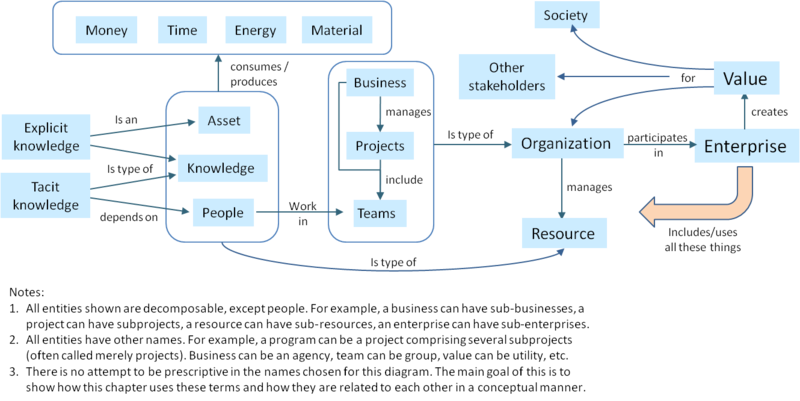

The figure below shows that an enterprise includes not only the organizations that participate in it, but also people, knowledge, and other assets such as processes, principles, policies, practices, doctrine, theories, beliefs, facilities, land, intellectual property, and so on.

Some enterprises organize from the top down, while others organize from the bottom up (i.e., they are self-organizing). Self-organizing enterprises are often more flexible and agile than if they were organized from above (Dyer and Ericksen 2009; Stacey 2006).

One type of enterprise architecture that supports agility is a non-hierarchical organization without a single point of control. Individuals function autonomously, constantly interacting with each other to define the work that needs to be done. Roles and responsibilities are not predetermined but rather emerge from individuals’ self-organizing activities and are constantly in flux. Similarly, projects are generated everywhere in the enterprise, sometimes even from outside affiliates. Key decisions are made collaboratively, on the spot, and on the fly. Because of this, knowledge, power, and intelligence are spread through the enterprise, making it uniquely capable of quickly recovering and adapting to the loss of any key enterprise component. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Business_agility)

Regardless of whether the enterprise of interest involves a single enterprise, or is an amalgamation of several participating organizations, SE has relevant tools and methods to help engineer the enterprise as a system.

Extended Enterprise

Sometimes it is prudent to consider a broader scope than merely the "boundaries" of the organizations involved in an enterprise. In some cases, it is necessary (and wise) to consider the "extended enterprise" in modeling, assessment, and decision making. This could include upstream suppliers, downstream consumers, and end user organizations, and perhaps even "sidestream" partners and key stakeholders. The extended enterprise can be defined as:

Wider organization representing all associated entities - customers, employees, suppliers, distributors, etc. - who directly or indirectly, formally or informally, collaborate in the design, development, production, and delivery of a product (or service) to the end user. (http://www.businessdictionary.com)

Enterprise Systems Engineering

Enterprise systems engineering (ESE), for the purpose of this article, is defined as:

The application of SE principles, concepts, and methods to the planning, design, improvement, and operation of an enterprise (see note 3).

To enable more efficient and effective enterprise transformation, the enterprise needs to be looked at “as a system,” rather than merely as a collection of functions connected solely by information systems and shared facilities (Rouse 2009). While a systems perspective is required for dealing with the enterprise, this is rarely the task or responsibility of people who call themselves systems engineers.

- Note 3. This form of systems engineering (i.e., ESE) includes (1) those traditional principles, concepts, and methods that work well in an enterprise environment, plus (2) an evolving set of newer ideas, precepts, and initiatives derived from complexity theory and the behavior of complex systems (such as those observed in nature and human languages).

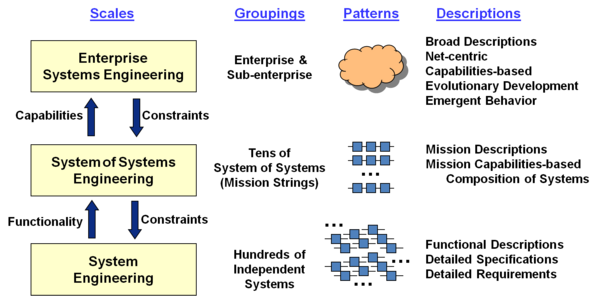

As shown in the figure below, some have made a distinction between the engineering of an enterprise and the engineering of a system of systems (SOS) (DeRosa 2005; Swarz et al. 2006). For more details on this see (Rebovich and White 2011).

Practical Considerations

When it comes to performing SE at the enterprise level, there are several good practices to keep in mind (Rebovich and White 2011):

- Set enterprise fitness as the key measure of system success. Leverage game theory and ecology, along with the practices of satisfying and governing the commons.

- Deal with uncertainty and conflict in the enterprise through adaptation: variety, selection, exploration, and experimentation.

- Leverage the practice of layered architectures with loose couplers and the theory of order and chaos in networks.

ESE differs from traditional SE (TSE) in a number of ways. The following are indicative of the differences although the distinctions are not always clear-cut:

- TSE usually covers the development and support of a single product or service. Although this is often through its entire life, the emphasis is more often on the earlier stages, up to and including initial deployment and use.

- TSE is not primarily concerned with interactions between products or services under development or use, whereas coping with the additional complexities which arise in these circumstances is a primary driver for ESE.

- TSE is assumed to take place in an organization which provides resources – for example defined process, trained individuals and finance – but is not explicitly transformed in the process.

- By comparison, enterprises do not have to have a defined start and an end. ESE is often about management of evolution in highly uncertain worlds, rather than following an end-to-end lifecycle driven by hard requirements.

- In ESE we treat the organization - and associated socio-technical issues, such as governance - as part of the system of interest and therefore requiring systematic design and transformation over time, to meet goals and objectives (which themselves may change over time).

- Policies and procedures are ways of moderating the behaviour of enterprise resources to meet strategic objectives, and are therefore included in the scope of ESE.

Overall, ESE seeks to engineer all the resources contained within the enterprise. While TSE, as described by ISO/IEC 15288 (2008) has a flexible SE lifecycle process model with the ability to depict interactions of organizations working in a number of different relationships, the standard assumes independence among the systems and services provided, except in so far as they draw upon common resources.

Enterprise governance involves shaping the political, operational, economic, and technical (POET) landscape. One should not try to control the enterprise like one would in a TSE effort at the project level. Some of the practical challenges and emerging solutions in the performance of ESE are covered by Brook and Riley (2012) and Rouse (2005).

References

Works Cited

Brook P., and T. Riley. 2012. "Enterprise Systems Engineering – Practical Challenges and Emerging Solutions." Paper presented at 22nd Annual International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) International Symposium, 9-12 July 2012, Rome, Italy.

CIO Council. 1999. Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework (FEAF). Washington, DC, USA: Chief Information Officer (CIO) Council.

DeRosa, J.K. 2005. “Enterprise Systems Engineering,” Presented at Air Force Association, Industry Day, Day 1, Danvers, MA, USA. 4 August 2005.

Dyer, L. and Ericksen, J. 2009. "Complexity-based Agile Enterprises: Putting Self-Organizing Emergence to Work." In A. Wilkinson et al (eds.). "The Sage Handbook of Human Resource Management." London, UK: Sage: 436–457.

Giachetti, R. E. 2010. "Design of Enterprise Systems: Theory, Architecture, and Methods." Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group.

ISO 15704. 2000. Industrial Automation Systems -- Requirements for Enterprise-Reference Architectures and Methodologies. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization (ISO), ISO 15704:2000.

McCaughin, K., and J.K. DeRosa. 2006. "Process in Enterprise Systems Engineering." Paper presented at 16th Annual International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) International Symposium, 9-13 July, 2006, Orlando, FL, USA.

MOD. 2004. Ministry of Defence Architecture Framework (MODAF), version 2. London, UK: U.K. Ministry of Defence.

Rebovich, G., and B. E. White, eds. 2011. "Enterprise Systems Engineering: Advances in the Theory and Practice." Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Auerbach.

Rouse, W. B. 2009. "Engineering the Enterprise as a System." In "Handbook of Systems Engineering and Management.", eds. A. P. Sage, W. B. Rouse. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Stacey, R. 2006. "The Science of Complexity: An Alternative Perspective for Strategic Change Processes." In R. MacIntosh et al (eds.). "Complexity and Organization: Readings and Concersations." London, UK: Routledge: 74–100.

Swarz, R. S. , J. K. DeRosa, and G. Rebovich 2006. “An Enterprise Systems Engineering Model,” INCOSE Symposium Proceedings.

Primary References

Bernus, P., Nemes L., and Schmidt G., eds. 2003. "Handbook on Enterprise Architecture," Berlin & Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

Rebovich, G. and B. E. White, eds. 2011. "Enterprise Systems Engineering: Advances in the Theory and Practice." Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Auerbach.

Rouse, W. B. 2005. "Enterprise as Systems: Essential Challenges and Enterprise Transformation." Systems Engineering, the Journal of the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) 8 (2): 138-50.

Rouse, W. B. 2009. "Engineering the Enterprise as a System." In "Handbook of Systems Engineering and Management.", eds. A. P. Sage, W. B. Rouse. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Valerdi, R. and Nightingale, D. J. 2011. "An Introduction to the Journal of Enterprise Transformation," Journal of Enterprise Transformation, 1(1), 1-6, 2011.

Additional References

Drucker, P. F. 1994. "The theory of business." Harvard Business Review (September/October 1994): 95-104.

Fox, M., J. F. Chionglo, and F. G. Fadel. 1993. "A common sense model of the enterprise." Paper presented at the 3rd Industrial Engineering Research Conference, Norcross, GA, USA.

Gøtze, J, ed. Journal of Enterprise Architecture. https://www.aogea.org/journal.

Joannou, P. 2007. "Enterprise, systems, and software—the need for integration." Computer, IEEE, May 2007.

MITRE. 2012. "Enterprise Engineering." In "Systems Engineering Guide." MITRE Corporation. http://www.mitre.org/work/systems_engineering/guide/enterprise_engineering/. Accessed 8 July 2012.

Nightingale, D., and J. Srinivasan. 2011. "Beyond the Lean Revolution: Achieving Successful and Sustainable Enterprise Transformation." New York, NY, USA: AMACOM Press.

Nightingale, D., and R. Valerdi, eds. Journal of Enterprise Transformation. London, UK: Taylor & Francis. http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/UJET.

SEBoK Discussion

Please provide your comments and feedback on the SEBoK below. You will need to log in to DISQUS using an existing account (e.g. Yahoo, Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) or create a DISQUS account. Simply type your comment in the text field below and DISQUS will guide you through the login or registration steps. Feedback will be archived and used for future updates to the SEBoK. If you provided a comment that is no longer listed, that comment has been adjudicated. You can view adjudication for comments submitted prior to SEBoK v. 1.0 at SEBoK Review and Adjudication. Later comments are addressed and changes are summarized in the Letter from the Editor and Acknowledgements and Release History.

If you would like to provide edits on this article, recommend new content, or make comments on the SEBoK as a whole, please see the SEBoK Sandbox.

blog comments powered by Disqus