Overview of the Systems Approach

Jackson and colleagues (2010, 41-43) define the Systems Approach as a set of top-level principles that provide the foundation of Systems Engineering. It implies taking a holistic (glossary) view of the system that includes the full life cycle as well as specific knowledge of systems engineering technical and management methods.

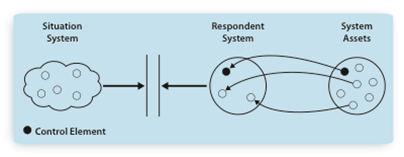

Lawson (2010) describes the relationship among the Systems Approach, Systems Thinking, and Systems Engineering as a mind-set to “think” and “act” in terms of systems. Developing this mind-set is promoted by several paradigms including the system coupling diagram , which includes the elements Situation System, Respondent System, and System Assets (Figure 1).

Figure 1. System Coupling Diagram

- Situation System – The problem or opportunity situation, either unplanned or planned. The situation may be the work of nature, man-made, a combination of both natural and man-made, or a postulated situation that is to be used as a basis for deeper understanding and training (for example, business games or military exercises).

- Respondent System – The system created to respond to the situation where the parallel bars indicate that this system interacts with the situation and transforms the situation to a new situation. A Respondent System, based upon the situation that is being treated, can have several names such as Project, Program, Mission, Task Force, or in a scientific context, Experiment. Note that one of the system elements of this system is a control element that directs the operation of the respondent system in its interaction with the situation. This element is based upon an instantiation of a Control System asset, for example a Command and Control System, or a control process of some form.

- System Assets – The sustained assets of one or more enterprises that are be utilized in responding to situations. System assets must be adequately life cycle managed so that when instantiated in a Respondent System will perform their function. These are the systems that are the primary objects for Systems Engineers. Examples of assets include concrete systems such as value added products or services, facilities, instruments and tools, abstract systems such as theories, knowledge, processes and methods.

This generic model portrays the essence of a system approach and is applicable to to Product Systems Engineering, Service Systems Engineering, and Enterprise Systems Engineering. Further, it is quite clear that this forms the basis for Systems of Systems where System Assets from multiple actors are collected in a Respondent System that is responding to a situation.

Since the premise is that Systems Approach is a mind-set prerequisite to Systems Engineering, it can be said that projects and programs executed with this mind-set are more likely to solve the problem or achieve the opportunity identified in the beginning.

The Systems Approach is often invoked in applications beyond product systems. For example, Systems Approach may be used in the educational domain. According to Biggs (1993), the system of interest includes “the student, the classroom, the institution, and the community.”

The Systems Approach must be viewed in the context of Systems Thinking as discussed by Checkland (1999) and by Edson (2008). According to Checkland (1999, 318), systems thinking is “an epistemology which, when applied to human activity is based on basic ideas of systems.”

Senge (1990) provides an expanded definition as follows: “Systems thinking is a discipline for seeing wholes. It is a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing patterns of change rather than static "snapshots." It is a set of general principles -- distilled over the course of the twentieth century, spanning fields as diverse as the physical and social sciences, engineering, and management. During the last thirty years, these tools have been applied to understand a wide range of corporate, urban, regional, economic, political, ecological, and even psychological systems. And systems thinking is a sensibility for the subtle interconnectedness that gives living systems their unique character.”

Systems Thinking has two parts. The first part is a set of principles and concepts to assist in learning how to think in terms of systems.

The second part of Systems Thinking is the how-to part. It is an abstract set of principles applied to problem situations and solution creation. This abstract set of principles is called the Systems Approach, the subject of this article. The systems approach relates System Thinking to:

- The exploration of potential problem or opportunity situations;

- The application of analysis , synthesis , and proving to system solutions;

- Ownership and use of systems within an enterprise .

All of the above are considered within a concurrent , recursive and iterative life cycle approach. Items 1 and 3 above are part of the business cycles of providing stakeholder value Ring (2004) within an enterprise, while item 2 can be mapped directly to product system , service system , and enterprise system Engineering. Note: a distinction is made here between the normal business of an enterprise and the longer term strategic activities of Enterprise Systems Engineering.

hard system and soft system tools and techniques suggested by Checkland (1999), Boardman and Sauser (2008), Senge (1990), and others are employed in this approach.

When parts of the approach are executed in the real world of an engineered system , a number of engineering and management disciplines emerge, including systems engineering .

SEBoK Parts 3 and 4 contain a detailed guide to Systems Engineering. A guide to the relationships between Systems Engineering and the organizations in Part 5 and between Systems Engineering and other disciplines in Part 6. More detailed discussion of how the System Approach relates to these engineering and management disciplines is included in the Applying the Systems Approach topic in this knowledge area.

References

Citations

Biggs, J.B. 1993. "From Theory to Practice: A Cognitive Systems Approach". Journal of Higher Education & Development.. Available from http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all~content=a758503083.

Boardman, J. and B. Sauser 2008. Systems Thinking - Coping with 21st Century Problems. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press.

Checkland, P. 1999. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

Edson, R. 2008. Systems Thinking. Applied. A Primer. Arlington, VA, USA: Applied Systems Thinking (ASysT) Institute, Analytic Services Inc.

Lawson, H. 2010. A Journey Through the Systems Landscape. London, UK: College Publications, Kings College.

Senge, P.M. 1990. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York, NY, USA: Doubleday/Currency.

Ring J. 2004. "Seeing an Enterprise as a System". INCOSE Insight' 6(2) (January 2004): 7-8.

Primary References

Boardman, J. and B. Sauser 2008. Systems Thinking: Coping with 21st Century Problems. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press.

Checkland, P. 1999. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

Senge, Peter. M. 1990. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday/Currency.

Additional References

Biggs, J.B. 1993. "From Theory to Practice: A Cognitive Systems Approach". Journal of Higher Education & Development.. Available from http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all~content=a758503083.

Edson, R. 2008. Systems Thinking. Applied. A Primer. Arlington, VA, USA: Applied Systems Thinking (ASysT) Institute, Analytic Services Inc.

Lawson, H. 2010. A Journey Through the Systems Landscape. London, UK: College Publications, Kings College.

Article Discussion

Review Comments

Signatures

--Radcock 11:53, 19 August 2011 (UTC)

--Apyster 12:31, 2 September 2011 (UTC)