Roles and Competencies

Enabling individuals to perform systems engineering (SE) requires understanding SE roles and competencies. Within a business or enterprise , SE responsibilities are allocated to individuals through the definition of SE roles. For an individual, a set of competencies enables the fulfillment of the assigned SE role.

SE competency is built from knowledge, skills, abilities, and attitudes (KSAA). These are developed through education, training, and experience. Traditionally, SE competencies have been developed primarily through experience. Recently, education and training have taken on a greater role in the development of SE competencies. SE competency must be viewed through the relationship to the system life cycle, the SE discipline, and the domain in which the engineer practices SE.

SE Competency Models

Individual competency models are typically used for one three purposes:

- Recruitment and Selection – Competency models define categories for behavioral-event interviewing, increasing the validity and reliability of selection and promotion decisions;

- Human Resources Planning and Placements – Competency models can be used to identify individuals to fill specific positions and/or identify gaps in key competency areas; or

- Education, Training, and Development – Explicit competency models let employees know what competencies are valued within their organization. Curriculum and interventions can be designed around desired competencies.

Application

No consensus on a specific competency model or small set of related competency models exists in the community. Many SE competency models have been developed for specific contexts or for specific organizations, and these models are useful within these contexts. However, users of models should be aware of the development method and context for the competency model they plan to use, since the primary competencies for one organization might be different than those for another organization. These models often are tailored to the specific business characteristics, including the specific product and service domain in which the organization operates. Each model typically includes a set of applicable competencies along with a scale for assessing the level of proficiency.

No single individual is expected to be proficient in all the competencies found in any model. The organization, overall, must satisfy the required proficiency in sufficient quantity to support business needs. Organizational competency is not a direct summation of the competency of the individuals on the organization, since organizational dynamics play an important role that can either raise or lower overall proficiency and performance. Enabling Teams to Perform Systems Engineering and Enabling Businesses and Enterprises to Perform Systems Engineering explore this.

Existing SE Competency Models

Though many organizations have proprietary SE competency models, there are several published SE competency models which can be used for reference. These include:

- The International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) UK Advisory Board model (Cowper and et al. 2005; INCOSE 2010b)

- The MITRE SE Competency model (MITRE 2007, 1-12)

- The SPRDE-SE/PSE model (DAU 2010); and

- The Academy of Program/Project & Engineering Leadership (APPEL) model (Menrad and Lawson 2008).

Other models and lists of traits include: (Hall 1962), (Frank 2000, 2002, 2006), (Kasser et al. 2009), (Squires et al. 2011), and (Armstrong et al. 2011). Ferris (2010) provides a summary and evaluation of the existing frameworks for personnel evaluation and for defining SE education. SE competencies can also be inferred from standards such as ISO-15288 (ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288) and from sources such as the INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook (INCOSE 2010a), the INCOSE Systems Engineering Certification Program, and CMMI criteria (SEI 2007). Table 1 lists information about several SE competency models. Each model was developed for a unique purpose within a specific context and validated in a particular way. It is important to understand the unique environment surrounding each competency model to determine its applicability in any new setting.

INCOSE Certification

"Certification is a formal process whereby a community of knowledgeable, experienced, and skilled representatives of an organization, such as the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), provides formal recognition that a person has achieved competency in specific areas (demonstrated by education, experience, and knowledge)." (INCOSE nd). The most popular credential in SE is offered by INCOSE, which requires an individual to pass a test to confirm knowledge of the field, requires experience in SE, and recommendations from those who have knowledge about the individual's capabilities and experience. Like all such credentials, the INCOSE certificate does not guarantee competence or suitability of an individual for a particular role, but is a positive indicator of an individual's ability to perform. Individual workforce needs often require additional KSAAs for any given systems engineer, but certification provides an acknowledged common baseline.

Commonality and Domain Expertise

SE competency models generally agree that systems thinking , taking a holistic view of the system that includes the full life cycle, and specific knowledge of both technical and managerial SE methods are required to be a fully capable systems engineer. It is also generally accepted that an accomplished systems engineer will have expertise in at least one domain of practice. General models, while recognizing the need for domain knowledge, typically do not define the competencies or skills related to a specific domain. Most organizations tailor such models to include specific domain KSAAs and other peculiarities of their organization.

However, a few domain- and industry-specific models have been created, such as the Aerospace Industry Competency Model (ETA 2010), published in draft form October 15, 2008 and now available online, developed by the Employment and Training Administration (ETA) in collaboration with the Aerospace Industries Association (AIA) and the National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA). This model for the aerospace industry is designed to evolve along with changing skill requirements. The ETA also provides numerous competency models for other industries through the ETA web sites (ETA 2010). The NASA Competency Management System (CMS) Dictionary is predominately a dictionary of domain-specific expertise required by the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to accomplish their space exploration mission (NASA 2006).

To provide specific examples for illustration, three SE competency model examples follow.

INCOSE SE Competency Model

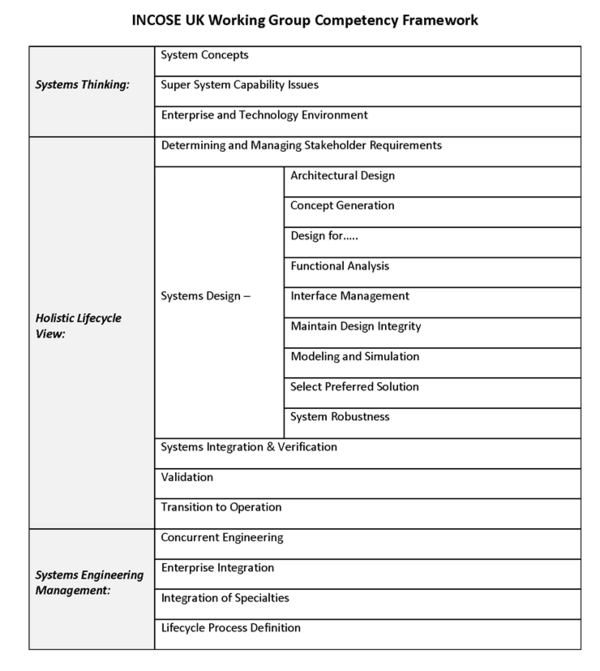

The INCOSE model was developed by a working group in the UK (Cowper and et al. 2005). As Table 2 shows, the INCOSE framework is divided into three theme areas - systems thinking, holistic life cycle view, and systems management - with a number of competencies in each. The INCOSE UK model was later adopted by the broader INCOSE organization (INCOSE 2010b).

United States DoD SE Competency Model

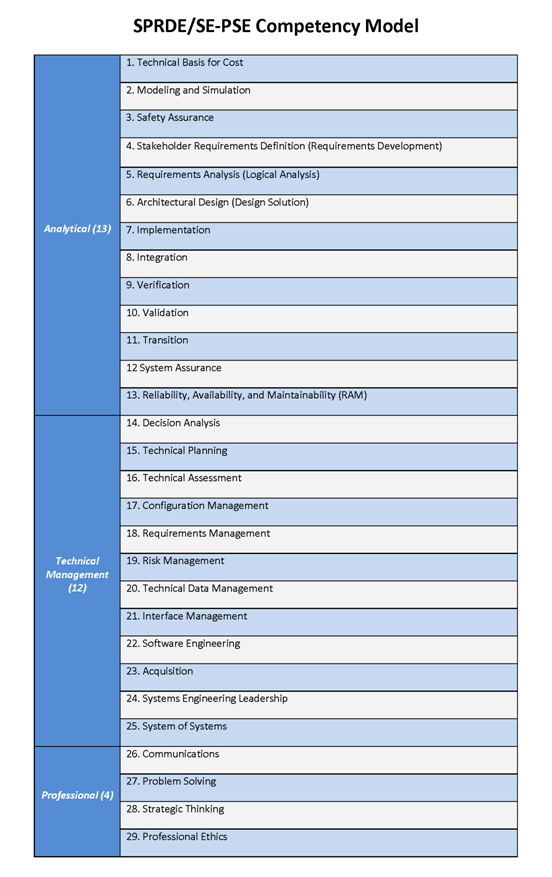

The model for US Department of Defense (DoD) SE acquisition professionals (SPRDE/SE-PSE) includes 29 competency areas, as shown in Table 3 (DAU 2010). Each is grouped according to a “Unit of Competence” as listed in the left-hand column. For this model, the three top-level groupings are analytical, technical management, and professional. The life cycle view used in the INCOSE model is evident in the SPRDE/SE-PSE analytical grouping, but is not cited explicitly. Technical management (TM) is the equivalent of the INCOSE SE management, but additional competencies are added, including software engineering competencies. Some general professional skills have been added to meet the needs for strong leadership required of the systems engineers and program managers who use this model.

NASA SE Competency Model

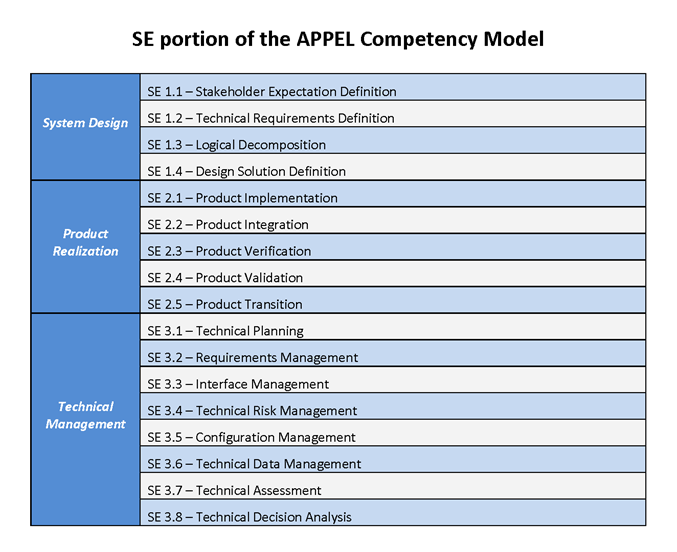

The US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) APPEL website provides a competency model that covers both project engineering and systems engineering (APPEL 2009). There are three parts to the model, one that is unique to project engineering, one that is unique to systems engineering, and a third that is common to both disciplines. Table 4 below shows the SE aspects of the model. The project management items include project conceptualization, resource management, project implementation, project closeout, and program control and evaluation. The common competency areas are NASA internal and external environments, human capital and management, security, safety and mission assurance, professional and leadership development, and knowledge management. This 2010 model is adapted from earlier versions. (Squires, Larson, and Sauser 2010, 246-260) offer a method that can be used to analyze the degree to which an organization’s SE capabilities meet government-industry defined SE needs.

Relationship of SE Competencies to Other Competencies

SE is one of many engineering disciplines. A competent SE must possess KSAAs that are unique, as well as many other KSAAs that are shared with other engineering and non-engineering disciplines.

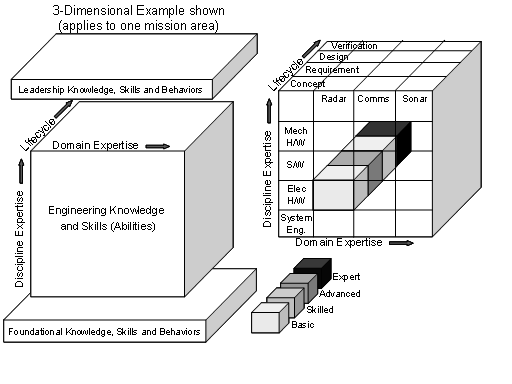

One approach for a complete engineering competency model framework has multiple dimensions where each of the dimensions has unique KSAAs that are independent of the other dimensions. (Wells 2008) The number of dimensions depends on the engineering organization and the range of work performed within the organization. The concept of creating independent axes for the competencies was presented in (Jansma and Derro 2007), using technical knowledge (domain/discipline specific), personal behaviors, and process as the three axes. An approach that uses process as a dimension is presented in (Widmann et al. 2000), where the competencies are mapped to process and process maturity models. For a large engineering organization that creates complex systems solutions, there are typically four dimensions:

- Discipline (e.g. electrical, mechanical, chemical, systems, optical, etc.),

- Life Cycle (e.g. requirements, design, testing, etc.),

- Domain (e.g. aerospace, ships, health, transportation, etc.), and

- Mission (e.g. air defense, naval warfare, rail transportation, border control, environmental protection, etc.).

These four dimensions are built on the concept defined in (Jansma and Derro 2007) and (Widmann et al. 2000) by separating discipline from domain and by adding mission and life cycle dimensions. Within many organizations, the mission may be consistent across the organization and this dimension would be unnecessary. A three-dimensional example is shown in Figure 1, where the organization works on only one mission area so that dimension has been eliminated from the framework.

The discipline, domain, and life cycle dimensions are included in this example, and some of the first-level areas in each of these dimensions are shown. At this level, an organization or an individual can indicate which areas are included in their existing or desired competencies. The sub-cubes are filled in by indicating the level of proficiency that exists or is required. For this example, blank indicates that the area is not applicable, and colors (shades of gray) are used to indicate the levels of expertise. The example shows a radar electrical designer that is an expert at hardware verification, is skilled at writing radar electrical requirements, and has some knowledge of electrical hardware concepts and detailed design. The radar electrical designer would also assess his or her proficiency in the other areas, the foundation layer, and the leadership layer to provide a complete assessment.

References

Works Cited

Academy of Program/Project & Engineering Leadership (APPEL). 2009. NASA's Systems Engineering Competencies. Washington, DC, USA: US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Accessed on September 15, 2011. Available at http://www.nasa.gov/offices/oce/appel/pm-development/pm_se_competency_framework.html.

Armstrong, J.R., D. Henry, K. Kepcher, and A. Pyster. 2011. "Competencies Required for Successful Acquisition of Large, Highly Complex Systems of Systems." Paper presented at 21st Annual International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) International Symposium (IS), 20-23 June 2011, Denver, CO, USA.

Cowper, D., S. Bennison, R. Allen-Shalless, K. Barnwell, S. Brown, A. El Fatatry, J. Hooper, S. Hudson, L. Oliver, and A. Smith. 2005. Systems Engineering Core Competencies Framework. Folkestone, UK: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) UK Advisory Board (UKAB).

DAU. 2010. SPRDE-SE/PSE Competency Assessment: Employee's User's Guide, 24 May 2010 version. in Defense Acquisition University (DAU)/U.S. Department of Defense Database Online. Accessed on September 15, 2011. Available at https://acc.dau.mil/adl/en-US/406177/file/54339/SPRDE-SE-PSE%20Competency%20Assessment%20Supervisors%20Users%20Guide_DAU.pdf.

ETA. 2010. Career One Stop: Competency Model Clearing House: Aerospace Competency Model. in Employment and Training Administration (ETA)/U.S. Department of Labor. Washington, DC, 2010. Accessed on September 15, 2011. Available at http://www.careeronestop.org//competencymodel/pyramid.aspx?AEO=Y.

Ferris, T.L.J. 2010. "Comparison of Systems Engineering Competency Frameworks." Paper presented at the 4th Asia-Pacific Conference on Systems Engineering (APCOSE), Systems Engineering: Collaboration for Intelligent Systems. 3-6 October 2010. Keelung, Taiwan.

Frank, M. 2000. "Engineering Systems Thinking and Systems Thinking." Systems Engineering 3(3): 163-168.

Frank, M. 2002. "Characteristics of Engineering Systems Thinking – A 3-D Approach for Curriculum Content." IEEE Transaction on System, Man, and Cybernetics. 32(3) Part C: 203-214.

Frank, M. 2006. "Knowledge, Abilities, Cognitive Characteristics and Behavioral Competences of Engineers with High Capacity for Engineering Systems Thinking (CEST)." Systems Engineering. 9(2): 91-103. [Republished in IEEE Engineering Management Review. 34(3)(2006):48-61].

Hall, A. D. 1962. A Methodology for Systems Engineering. Princeton, NJ, USA: D. Van Nostrand Company Inc.

INCOSE. nd. "History of INCOSE Certification Program." Accessed September 9, 2011. Available at http://www.incose.org/educationcareers/certification/csephistory.aspx.

INCOSE. 2011a. Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities, version 3.2.1. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.2.1.

INCOSE. 2010b. Systems Engineering Competencies Framework 2010-0205. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2010-003.

Jansma, P.A. and M.E. Derro. 2007. "If You Want Good Systems Engineers, Sometimes You Have to Grow Your Own!." Paper presented at IEEE Aerospace Conference. 3-10 March, 2007. Big Sky, MT, USA.

Kasser, J.E., D. Hitchins, and T.V. Huynh. 2009. "Reengineering Systems Engineering." Paper presented at the 3rd Annual Asia-Pacific Conference on Systems Engineering (APCOSE). 2009. Singapore.

Menrad, R. and H. Lawson. 2008. "Development of a NASA Integrated Technical Workforce Career Development Model Entitled: Requisite Occupation Competencies and Knowledge – The ROCK." Paper presented at the 59th International Astronautical Congress (IAC), 29 September-3 October, 2008. Glasgow, Scotland.

MITRE. 2007. "Enterprise Architecting for Enterprise Systems Engineering." Warrendale, PA, USA: SEPO Collaborations, SAE International. June 2007.

NASA. 2006. NASA Competency Management Systems (CMS): Workforce Competency Dictionary, revision 6a. In U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Washington, D.C. Accessed on September 15, 2011. Available at http://ohr.gsfc.nasa.gov/cms/CMS-DOC-01_Rev6a_NASA_CompetencyDictionary.doc.

SEI. 2007. Capability Maturity Model Integrated (CMMI) for Development, version 1.2, Measurement and Analysis Process Area. Pittsburg, PA, USA: Software Engineering Institute (SEI)/Carnegie Mellon University (CMU).

Squires, A., W. Larson, and B. Sauser. 2010. "Mapping space-based systems engineering curriculum to government-industry vetted competencies for improved organizational performance." Systems Engineering. 13 (3): 246-260. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/sys.20146.

Squires, A., J. Wade, P. Dominick, and D. Gelosh. 2011. "Building a Competency Taxonomy to Guide Experience Acceleration of Lead Program Systems Engineers." Paper presented at CSER 2011. 15-16 April 2011. Los Angeles, CA.

Wells, B. H. 2008. "A Multi-Dimensional Hierarchical Engineering Competency Model Framework." Paper presented at IEEE International Systems Conference. March 2008. Montreal, Canada.

Widmann, E.R., G.E. Anderson, G.J. Hudak, and T.A. Hudak. 2000. "The Taxonomy of Systems Engineering Competency for The New Millennium." Presented at 10th Annual INCOSE Internal Symposium. 16-20 July 2000. Minneapolis, MN, USA.

Primary References

Academy of Program/Project & Engineering Leadership (APPEL). 2009. NASA's Systems Engineering Competencies. Washington, DC, USA: US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Accessed on September 15, 2011. Available at http://www.nasa.gov/offices/oce/appel/pm-development/pm_se_competency_framework.html.

DAU. 2010. SPRDE-SE/PSE Competency Assessment: Employee's User's Guide, 24 May 2010 version. in Defense Acquisition University (DAU)/U.S. Department of Defense Database Online. Accessed on September 15, 2011. Available at https://acc.dau.mil/adl/en-US/406177/file/54339/SPRDE-SE-PSE%20Competency%20Assessment%20Supervisors%20Users%20Guide_DAU.pdf.

INCOSE. 2010. Systems Engineering Competencies Framework 2010-0205. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2010-003.

Additional References

No additional references have been identified for version 0.75. Please provide any recommendations on additional references in your review.

SEBoK Discussion

Please provide your comments and feedback on the SEBoK below. You will need to log in to DISQUS using an existing account (e.g. Yahoo, Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) or create a DISQUS account. Simply type your comment in the text field below and DISQUS will guide you through the login or registration steps. Feedback will be archived and used for future updates to the SEBoK. If you provided a comment that is no longer listed, that comment has been adjudicated. You can view adjudication for comments submitted prior to SEBoK v. 1.0 at SEBoK Review and Adjudication. Later comments are addressed and changes are summarized in the Letter from the Editor and Acknowledgements and Release History.

If you would like to provide edits on this article, recommend new content, or make comments on the SEBoK as a whole, please see the SEBoK Sandbox.

blog comments powered by Disqus