System Resilience

According to the Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles (1973), resilience is “the act of rebounding or springing back.” This definition most directly fits the situation of materials which return to their original shape after deformation. For human-made, or engineered systems the definition of resilience can be extended to include the ability to maintain capability in the face of a disruption . The US government definition for resilient infrastructure systems is the "ability of systems, infrastructures, government, business, communities, and individuals to resist, tolerate, absorb, recover from, prepare for, or adapt to an adverse occurrence that causes harm, destruction, or loss of national significance” (DHS 2010).

The name Resilience Engineering was coined in the book Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts (Hollnagel et al 2006). The authors make clear in this book that Resilience Engineering has to do with the resilience of the organisations that design and operate engineered systems and not with the systems themselves The term System Resilience used in this article is primarily concerned with the techniques used to consider the resilience of engineered systems directly. To fully achieve this SE also needs to consider the resilience of those organisational and human systems which enable the life cycle of an engineered system. The techniques or design principles used to assess and improve the resilience of engineered systems across their life cycle are elaborated by Jackson and Ferris (2013).

Overview

Resilience is a relatively new term in the SE realm, appearing only in the 2006 time frame and becoming popularized in 2010. The recent application of “resilience” to engineered systems has led to confusion over its meaning and a proliferation of alternative definitions. (One expert claims that well over 100 unique definitions of resilience have appeared.) While the details of definitions will continue to be discussed and debated, the information here should provide a working understanding of the meaning and implementation of resilience, sufficient for a system engineer to effectively address it.

Definition

It is difficult to identify a single definition that – word for word – satisfies all. However, it is possible to gain general agreement of what is meant by resilience of engineered systems; viz., resilience is the ability to provide required capability in the face of adversity.

Scope of the Means

In applying this definition, one needs to consider the range of means by which resilience is achieved: The means of achieving resilience include avoiding, withstanding, recovering from and evolving and adapting to adversity. These may also be considered the fundamental objectives of resilience, Brtis (2013). Classically, resilience includes “withstanding” and “recovering” from adversity. For the purpose of engineered systems, “avoiding” adversity is considered a legitimate means of achieving resilience. Jackson and Ferris (2016). Also, it is believed that resilience should consider the system’s ability to “evolve and adapt” to future threats and unknown-unknowns.

Scope of the Adversity

Adversity is any condition that may degrade the desired capability of a system. We propose that the SE must consider all sources and types of adversity; e.g., from environmental sources, due to normal failure, as well as from opponents, friendlies and neutral parties. Adversity from human sources may be malicious or accidental. Adversities may be expected or not. Adversity may include "unknown unknowns." The techniques for achieving resilience discussed below are applicable to both hostile and non-hostile adversities in both civil and military domains. Non-hostile adversities will dominate in the civil domain and hostile adversities will predominate in the military domain.

Notably, a single incident may be the result of multiple adversities, such as a human error committed in the attempt to recover from another adversity.

Jackson & Ferris Taxonomy

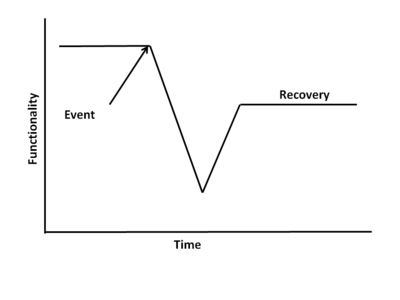

Figure 1 depicts the loss and recovery of the functionality of a system. In the taxonomy proposed by Jackson and Ferris (2013) four attributes can lead to a resilient system and may posess four attributes: robustness , adaptability , tolerance , and integrity — and fourteen design techniques and 20 support techniques that can achieve these attributes. These four attributes are adapted from Hollnagel, Woods, and Leveson (2006), and the design techniques are extracted from Hollnagel et al. and are elaborated based on Jackson and Ferris (2013) for civil systems.

Other sources for example, DHS (2010) lists the following additional attributes: rapidly, affordability and learning capacity.

The Robustness Attribute

Robustness is the attribute of a system that allows it to withstand a threat in the normal operating state. Resilience allows that the capacity of a system may be exceeded, forcing the system to rely on the remaining attributes to achieve recovery. The following design techniques tend to achieve robustness:

The Adaptability Attribute

Adaptability is the attribute of a system that allows it to restructure itself in the face of a threat. Adaptability can apply to any phase of the event including detecting and avoiding the adversity and restructuring to return to normal operation. The following design techniques apply to the adaptability attribute:

The Tolerance Attribute

Tolerance is the attribute of a system that allows it to degrade gracefully following an encounter with adversity. The following design techniques apply to the tolerance attribute.

The Integrity Attribute

Integrity is the attribute of a system that allows it to operate before, during, and after an encounter with a threat. Integrity is also called cohesion which according to (Hitchins 2009), a basic characteristic of a system. The following global design technique applies to the integrity attribute.

MITRE Taxonomy

Brits (2016) builds on the cyber resilience work of Bodeau & Graubart (2011) and proposes an objectives-based three layer taxonomy for thinking about resilience. The three layers include: 1) four fundamental objectives of resilience, 2) ten means objectives of resilience, and, 3) 23 engineering techniques for achieving resilience.

The four fundamental objectives, which identify the intrinsic value of resilience, are:

- Avoid adversity

- Withstand adversity

- Recover from adversity

- Evolve and adapt to unanticipated adversity

The ten means objectives are not ends in themselves - as are the fundamental objective - but do tend to result in the achievement of the fundamental objectives: The means objectives are:

- anticipate

- understand

- disaggregate

- prepare

- prevent

- continue

- constrain

- redeploy

- transform

- re-architect

The 23 engineering techniques that tend to achieve the fundamental objectives are:

- adaptive response

- analytic monitoring

- coordinated defense

- deception

- distribution

- detection avoidance

- diversification

- dynamic positioning

- dynamic representation

- effect tolerance

- non-persistence

- privilege restriction

- proliferation

- protection

- realignment

- reconfiguring

- redundancy

- replacement

- segmentation

- substantiated integrity

- substitution

- threat suppression

- unpredictability

The relationships between the three layers of this taxonomy are many-to-many relationships.

The Jackson & Ferris taxonomy comes from the civil resilience perspective and the Brtis/MITRE taxonomy comes from the military perspective. Jackson and Brtis (2017) have shown that many of the techniques of the two taxonomies are equivalent and that some techniques are unique to each domain.

Techniques for Achieving Resilience

Techniques for achieving resilience have been identified for both the civil and military domains. Jackson and Ferris (2013) have identified techniques for the civil domain and Brtis (2016) has identified techniques for the military domain. There is overlap between these two sets and also some differences. Jackson and Brtis (2017) compare the techniques in the two domains and show their commonalities and their differences.

Techniques for the Civil Domain

34 techniques and support techniques for the civil domain described by Jackson and Ferris (2013) include both design and process techniques that will be used to define a system of interest in an effort to make it resilient. These techniques were extracted from many sources. Prominent among these sources is Hollnagel et al (2006). Other sources include Leveson (1995), Reason (1997), Perrow (1999), and Billings (1997). Some techniques were implied in case study reports, such as the 9/11 Commission report (2004) and the US-Canada Task Force report (2004) following the 2003 blackout. These techniques include very simple and well-known techniques as physical redundancy and more sophisticated techniques as loose coupling. Some of these techniques are domain dependent, such as loose coupling, which is important in the power distribution domain as discussed by Perrow (1999). These techniques will be the input to the state model of Jackson, Cook, and Ferris (2015) to determine the characteristics of a given system for a given threat. In the resilience literature the term technique is used to describe both scientifically accepted techniques and also heuristics, design rules determined from experience as described by Rechtin (1991). Jackson and Ferris (2013) showed that it is often necessary to invoke these techniques in combinations to best enhance resilience. This concept is called defense in depth. Pariès (2011) illustrates how defense in depth was used to achieve resilience in the 2009 ditching of US Airways Flight 1549. Uday and Marais (2015) apply the above techniques to the design of a system-of-systems. Henry and Ramirez-Marquez (2016) describe the state of the U.S. East Coast infrastructure in resilience terms following the impact of Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Bodeau & Graubert (2011) propose a framework for understanding and addressing cyber-resilience. They propose a taxonomy comprised of four goals, eight objectives, and fourteen cyber-resilience techniques. Many of these goals, objectives and practices can be applied to non-cyber resilience. Jackson and Ferris (2013) have collected 14 design techniques from various authoritative sources. These techniques are applicable primarily to civil systems including civil infrastructure, aviation, and power grids. In addition to the 14 design techniques, Jackson and Ferris (2013) also identify 20 support techniques that are narrower in scope than the above design techniques.

Techniques for the Military Domain

Brtis (2016), in the third level of his taxonomy discussed above identifies 23 engineering techniques for achieving resilience in the military domain. Jackson and Brtis (2017) have shown that many of the civil and military techniques are equivalent though some are unique to each domain.

The Resilience Process

Implementation of resilience in a system requires the execution of both analytic and holistic processes. In particular, the use of architecting with the associated heuristics is required. Inputs are the desired level of resilience and the characteristics of a threat or disruption. Outputs are the characteristics of the system, particularly the architectural characteristics and the nature of the elements (e.g., hardware, software, or humans). Artifacts depend on the domain of the system. For technological systems, specification and architectural descriptions will result. For enterprise systems, enterprise plans will result. Both analytic and holistic methods, including the techniques of architecting, are required. Analytic methods determine required robustness. Holistic methods determine required adaptability, tolerance, and integrity. One pitfall is to depend on just a single technique to achieving resilience. The technique of defense in depth suggests that multiple techniques may be required to achieve resilience.

Practical Considerations

Resilience is difficult to achieve for infrastructure systems because the nodes (cities, counties, states, and private entities) are reluctant to cooperate with each other. Another barrier to resilience is cost. For example, achieving redundancy in dams and levees can be prohibitively expensive. Other aspects, such as communicating on common frequencies, can be low or moderate cost; even there, cultural barriers have to be overcome for implementation.

System Description

System resilience is the ability of a engineered system to provide required capability in the face of adversity . Resilience in the realm of systems engineering involves identifying: 1) the capabilities that are required of the system, 2) the adverse conditions under which the system is required to deliver those capabilities, and 3) the systems engineering to ensure that the system can provide the required capabilities.

Put simply, resilience is achieved by a systems engineering focus on adverse conditions.

Resilience of Processes

It is important to recognize that processes are systems – in fact Systems Engineering is a system. Discussions relating to the resilience of such “process” systems include seven key resiliencies that successful sociotechnical systems intending to accomplish system engineering must have, Warfield (2008). Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety and Pareto’s Law of Requisite Saliency are the most familiar. The scope and time of arrival of Contract Change Orders that require system engineering attention pose significant risk. Ones that occur during detailed design that affect the requirements baseline and system design baseline and occur faster than can be accommodated are particularly threatening.

Discipline Management

Most enterprises, both military and commercial, include organizations generally known as Advanced Design. These organizations are responsible for defining the architecture of a system at the very highest level of the system architecture. This architecture reflects the resilience techniques described in Jackson and Ferris (2013) and Brtis (2016) and the processes associated with that system. In many domains, such as fire protection, no such organization will exist. However, the system architecture will still need to be defined by the highest level of management in that organization. In addition, some aspects of resilience will be established by government imposed requirements.

Discipline Relationships

Interactions

Outputs

The primary outputs of the resilience discipline are a subset of the principles described by Jackson and Ferris (2013) which have been determined to be appropriate for a given system, threat, and desired state of resilience as determined by the state-transition analysis described below. The processes requiring these outputs are the system design and system architecture processes.

Inputs

Inputs to the state model described in Jackson, Cook, and Ferris (2015) include (1) type of system of interest, (2) nature of threats to the system (earthquakes, terrorist threats, human error, etc.) (3) techniques for potential architectural design, and (4) predicted probability of success of individual techniques.

Dependencies

The techniques identified for the achieving resilience may also be used by other systems engineering areas of concern such as safety, reliability, human factors, availability, maintainability, human factors, security, and others. For example, the physical redundancy technique may help achieve resilience, reliability, and safety. Resilience design and analysis should be conducted in concert with the various ‘ilities. The goal being to create a system which -- from the beginning -- meets the requirements for resilience and other ‘ilities.

Discipline Standards

ASIS (2009) has published a standard pertaining to the resilience of organizational systems.

NIST 800-160 considers resilience of physical systems.

Personnel Considerations

Humans are important components of systems for which resilience is desired. This aspect is reflected in the human in the loop technique identified by Jackson and Ferris (2013). Decisions made by the humans are at the discretion of the humans in real time. Apollo 11 described by Eyles (2009) is a good example.

Metrics

Uday & Marais (2015) performed a survey of resilience metrics. Those identified include:

- Time duration of failure

- Time duration of recovery

- Ratio of performance recovery to performance loss

- A function of speed of recovery

- Performance before and after the disruption and recovery actions

- System importance measures

Jackson (2016) developed a metric to evaluate various systems in four domains: aviation, fire protection, rail, and power distribution, for the principles that were lacking in ten different case studies. The principles are from the set identified by Jackson and Ferris (2013) and are represented in the form of a histogram plotting principles against frequency of omission. The data in these gaps were taken from case studies in which the lack of principles was inferred from recommendations by domain experts in the various cases cited.

Brtis (2016) surveyed and evaluated a number of potential resilience metrics and identified the following: [Note: This reference is going through approval for public release and should be referenceable by the end of July 2016.]

- Maximum outage period

- Maximum brownout period

- Maximum outage depth

- Expected value of capability: the probability-weighted average of capability delivered

- Threat resiliency (the time integrated ratio of the capability provided divided by the minimum needed capability)

- Expected availability of required capability (the likelihood that for a given adverse environment the required capability level will be available)

- Resilience levels (the ability to provide required capability in a hierarchy of increasingly difficult adversity)

- Cost to the opponent

- Cost-benefit to the opponent

- Resource resiliency (the degradation of capability that occurs as successive contributing assets are lost)

Brtis found that multiple metrics may be required, depending on the situation. However, if one had to select a single most effective metric for reflecting the meaning of resilience, it would be the expected availability of the required capability. Expected availability of the required capability is the probability-weighted sum of the availability summed across the scenarios under consideration. In its most basic form, this metric can be represented mathematically as:

<math>

R = \sum_{1}^{n} \left ( \frac{^{P_{i}}}{T} \int_{0}^{T} Cr(t)_{i}, dt\right )

</math>

where,

R = Resilience of the required capability (Cr);

n = the number of exhaustive and mutually exclusive adversity scenarios within a context (n can equal 1);

Pi = the probability of adversity scenario I;

Cr(t)_i = timewise availability of the required capability during scenario I; --- 0 if below the required level --- 1 if at or above the required value (Where circumstances dictate this may take on a more complex, non-binary function of time.);

T = length of the time of interest.

Models

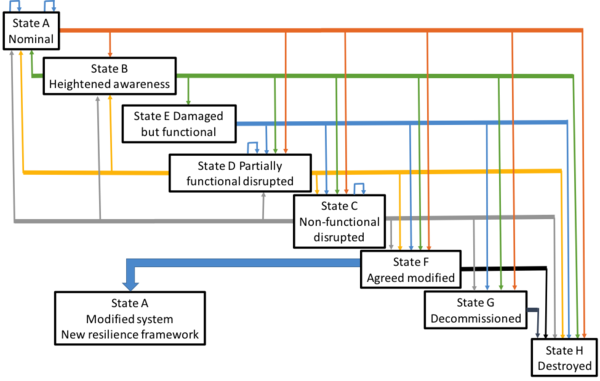

The state-transition model described by Jackson et al (2015) describes a system in its various states before, during, and after an encounter with a threat. The model identifies seven different states as the system passes from a nominal operational state to minimally acceptable functional state as shown in the figure below. In addition, the model identifies 28 transition paths from state to state. To accomplish each transition the designer must invoke one or more of the 34 principles or support principles described by Jackson and Ferris (2013). The designs implied by these principles can then be entered into a simulation to determine the total effectiveness of each design.

Tools

No tools dedicated to resilience have been identified.

Practical Considerations

Pitfalls

Information to be provided at a later date.

Proven Practices

Information to be provided at a later date.

Other Considerations

Information to be provided at a later date.

References

Works Cited

9/11 Commission. (2004). 9/11 Commission Report.

ASIS International. (2009). Organizational Resilience: Security, Preparedness, and Continuity Management Systems--Requirements With Guidance for Use. Alexandria, VA, USA: ASIS International.

Billings, C. (1997). Aviation Automation: The Search for Human-Centered Approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bodeau, D. K, & Graubart, R. (2011). Cyber Resiliency Engineering Framework, MITRE Technical Report #110237, The MITRE Corporation.

Brtis, J. S. (2016). How to Think About Resilience, MITRE Technical Report, MITRE Corporation.

Hollnagel, E., D. Woods, and N. Leveson (eds). 2006. Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

INCOSE (2015). Systems Engineering Handbook, a Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities. San Diego, Wiley.

Jackson, S., & Ferris, T. (2013). Resilience Principles for Engineered Systems. Systems Engineering, 16(2), 152-164.

Jackson, S., Cook, S. C., & Ferris, T. (2015). A Generic State-Machine Model of System Resilience. Insight, 18.

Jackson, S. & Ferris, T. L. (2016). Proactive and Reactive Resilience: A Comparison of Perspectives.

Jackson, W. S. (2016). Evaluation of Resilience Principles for Engineered Systems. Unpublished PhD, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia.

Leveson, N. (1995). Safeware: System Safety and Computers. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison Wesley.

Madni, Azad,, & Jackson, S. (2009). Towards a conceptual framework for resilience engineering. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Systems Journal, 3(2), 181-191.

Pariès, J. (2011). Lessons from the Hudson. In E. Hollnagel, J. Pariès, D. D. Woods & J. Wreathhall (Eds.), Resilience Engineering in Practice: A Guidebook. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Perrow, C. (1999). Normal Accidents: Living With High Risk Technologies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Reason, J. (1997). Managing the Risks of Organisational Accidents. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Rechtin, E. (1991). Systems Architecting: Creating and Building Complex Systems. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: CRC Press.

US-Canada Power System Outage Task Force. (2004). Final Report on the August 14, 2003 Blackout in the United States and Canada: Causes and Recommendations. Washington-Ottawa.

Uday, P., & Morais, K. (2015). Designing Resilient Systems-of-Systems: A Survey of Metrics, Methods, and Challenges. Systems Engineering, 18(5), 491-510.

Warfield, J. N. (2008) "A Challenge for Systems Engineers: To Evolve Toward Systems Science" INCOSE INSIGHT, Volume 11, Issue 1, January 2008.

Primary References

Hollnagel, E., Woods, D. D., & Leveson, N. (Eds.). (2006). Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Jackson, S., & Ferris, T. (2013). Resilience Principles for Engineered Systems. Systems Engineering, 16(2), 152-164.

Jackson, S., Cook, S. C., & Ferris, T. (2015). Towards a Method to Describe Resilience to Assist in System Specification. Paper presented at the INCOSE Systems 2015.

Jackson, S.: Principles for Resilient Design - A Guide for Understanding and Implementation. Available at https://www.irgc.org/irgc-resource-guide-on-resilience Accessed 18th August 2016

Madni, Azad,, & Jackson, S. (2009). Towards a conceptual framework for resilience engineering. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Systems Journal, 3(2), 181-191.

Additional References

ASIS International. 2009. Organisational Resilience: Security, Preparedness, and Continuity Management Systems--Requirements With Guidance for Use. Alexandria, VA, USA: ASIS International.

Billings, Charles. 1997. Aviation Automation: The Search for Human-Centered Approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bodeu, D. K., and R. Graubart. 2011. Cyber Resiliency Engineering Framework.

Eyles, Don. 2009. "1202 Computer Error Almost Aborted Lunar Landing." Massachusetts Intitute of Technology, MIT News, accessed 6 April http://njnnetwork.com/2009/07/1202-computer-error-almost-aborted-lunar-landing/

Henry, Devanandham, and Emmanual Ramirez-Marquez. 2016. "On the Impacts of Power Outages during Hurrican Sandy -- A Resilience Based Analysis." Systems Engineering 19 (1):59-75.

OED. 1973. The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles. edited by C. T. Onions. Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press. Original edition, 1933.

Pariès, Jean. 2011. "Lessons from the Hudson." In Resilience Engineering in Practice: A Guidebook, edited by Erik Hollnagel, Jean Pariès, David D. Woods and John Wreathhall, 9-27. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Rechtin, Eberhardt. 1991. Systems Architecting: Creating and Building Complex Systems. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: CRC Press.

Uday, Payuna, and Karen Morais. 2015. "Designing Resilient Systems-of-Systems: A Survey of Metrics, Methods, and Challenges." Systems Engineering 18 (5):491-510.