Technical Leadership in Systems Engineering

Technical leadership in systems engineering is exhibited by effectively communicating a vision, strategy, method, or technique needed to achieve a shared goal, which is accepted and enacted by team members, technical personnel, managers, and other project/program stakeholders. A systems engineering leader may lead a team of systems engineers for a project or program, or may be the only systems engineer who leads a team of members from the various disciplines involved in the project or program (e.g., other engineers, IT personnel, service providers). There is a vast amount of literature addressing leadership issues from multiple points of view, including philosophical, psychological, and emotional considerations (Yukl 2013). This article is concerned with the pragmatic aspects of the leading team members involved in a systems engineering project. Related knowledge areas and articles are in Part 5 Enabling Systems Engineering and the Part 6 knowledge area Systems Engineering and Project Management.

Attributes of Effective Leaders

Some commonly cited attributes of effective leaders are listed in Table 1 below.

| Listening carefully | Maintaining enthusiasm |

| Delegating authority | Saying “thank you” |

| Facilitating teamwork | Praising team for achievements |

| Coordinating work activities | Accepting responsibility for shortcomings |

| Facilitating communication | Coaching and training |

| Making timely decisions | Indoctrinating newly assigned personnel |

| Involving appropriate stakeholders | Reconciling differences and resolving conflicts |

| Speaking with individual team members on a frequent basis | Helping team members develop career paths and achieve professional goals |

| Working effectively with the project/program manager and external stakeholders | Reassigning, transferring, and terminating personnel as necessary |

Characteristics that result in effective leadership of systems engineering activities include behavioral attributes, leadership style, and communication style. In addition, a team leader for a systems engineering project or program has management responsibilities that include, but are not limited to: developing and maintaining the systems engineering plan, as well as establishing and overseeing the relationships between the project/program manager and project/program management personnel.

Behavioral Attributes

Behavioral attributes are habitual patterns of behavior, thought, and emotion that remain stable over time (Yukl 2013). Positive behavioral attributes enable a systems engineering leader to communicate effectively and to make sound decisions, while also taking into consideration the concerns of all stakeholders. Desirable behavioral attributes for a systems engineering leader include characteristics such as (Fairley 2009):

- Aptitude - This is exhibited by the ability to effectively lead a team. Leadership aptitude is not the same as knowledge or skill but rather is indicative of the ability (either intuitive or learned) to influence others. Leadership aptitude is sometimes referred to as charisma or as an engaging style.

- Initiative - This is exhibited by enthusiastically starting and following through on every leadership activity.

- Enthusiasm - This is exhibited by expressing and communicating a positive, yet realistic attitude concerning the project, product, and stakeholders.

- Communication Skills - These are exhibited by expressing concepts, thoughts, and ideas in a clear and concise manner, in oral and written forms, while interacting with colleagues, team members, managers, project stakeholders, and others.

- Team Participation - This is exhibited by working enthusiastically with team members and others when collaborating on shared work activities.

- Negotiation - This is the ability to reconcile differing points of view and achieve consensus decisions that are satisfactory to the involved stakeholders.

- Goal Orientation – This involves setting challenging but not impossible goals for oneself, team members, and teams.

- Trustworthiness - This is demonstrated over time by exhibiting ethical behavior, honesty, integrity, and dependability in taking actions and making decisions that affect others.

Weakness, on the other hand, is one example of a behavioral attribute that may limit the effectiveness of a systems engineering team leader.

Personality Traits

“Personality traits” was initially introduced in the early 1900's by Carl Jung, who published a theory of personality based on three continuums: introversion-extroversion, sensing-intuiting, and thinking-feeling. According to Jung, each individual has a dominant style which includes an element from each of the three continuums. Jung also emphasized that individuals vary their personality traits in the context of different situations; however, an individual’s dominant style is the preferred one, as it is the least stressful for the individual to express and it is also the style that an individual will resort to when under stress (Jung 1971). The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), developed by Katherine Briggs and her daughter Isabel Myers, includes Jung’s three continuums, plus a forth continuum of judging-perceiving. These four dimensions characterize 16 personality styles for individuals designated by letters, such as ISTP (Introverted, Sensing, Thinking, and Perceiving). An individual’s personality type indicator is determined through the answers the person has provided on a questionnaire (Myers 1995). MBTI profiles are widely used by job counselors to match an individual’s personality type to job categories in which the individual would be "most comfortable and effective”. Matching is based on the results of having applied the MBTI model to several thousands of subjects who have described themselves as comfortable and effective in their jobs. The MBTI has also been applied to group dynamics and leadership styles. Most studies indicate that groups perform better when a mixture of personality styles work together to provide different perspectives. Some researchers claim that there is evidence suggests that positive leadership styles are most closely related to an individual’s position on the judging-perceiving scale of the MBTI profile (Hammer 2001). Those on the judging side of the scale are most likely to be “by the book” managers, while those on the perceiving side of the scale are most likely to be “people-oriented” leaders. “Judging” in the MBTI model does not mean judgmental; rather, a judging trait indicates a quantitative orientation and a perceiving trait indicates a qualitative orientation. The MBTI has its detractors (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myers-Briggs_Type_Indicator#Criticism), (Nowack 1996); however, MBTI personality styles can provide insight into effective and ineffective modes of interaction and communication among team members and team leaders. For example, an individual with a strongly Introverted, Thinking, Sensing, and Judging personality index (ITSJ) may have difficulty interacting with an individual who has a strongly Extroverted, Intuiting, Feeling, Perceiving personality index (ENFP).

Leadership Styles and Communication Styles

There is a vast amount of literature pertaining to leadership styles and there are many models of leadership. Most of these leadership models are based on some variant of Jung’s psychological types. One of the models, the Wilson Social Styles, integrates leadership styles and communication styles (Wilson 2004). The Wilson model characterizes four kinds of leadership styles:

- Driver leadership style - This is exhibited when a leader focuses on the work to be accomplished and on specifying how others must do their jobs.

- Analytical-style leadership - This emphasizes collecting, analyzing, and sharing data and information. An analytical leader asks others for their opinions and recommendations to gather information.

- Amiable leadership style – This is characterized by emphasis on personal interactions and on asking others for their opinions and recommendations.

- Expressive leadership style – Like the amiable style, this also focuses on personal relationships, but an expressive leader tells others rather than asking for opinions and recommendations.

When taken to extremes, each of these styles can result in weakness of leadership. By focusing too intently on the work, "drivers" can provide too much or too little guidance and direction. Too little guidance occurs when the individual is preoccupied with her or his personal work, while too much guidance results in micromanagement, which limits the personal discretion for team members. Drivers may also be insensitive to interpersonal relationships with team members and others. Analytical leaders may provide too much information or may fail to provide information that is obvious to them, but not their team members. They do not like to discuss things they already know or that are irrelevant to the task at hand. Like driver-style leaders, they may be insensitive to interpersonal relationships with other individuals. Amiable leaders focus on interpersonal relationships in order to get the job done. They may exhibit a dislike of those who fail to interact with them on a personal level and may fail to show little concern for those who show little personal interest in them. Expressive leaders also focus on interpersonal relationships. In the extreme, an expressive leader may be more interested in stating their opinions than in listening to others. Additionally, they may play favorites and ignore those who are not favorites. While these characterizations are gross oversimplifications, they serve to illustrate leadership styles that may be exhibited by systems engineering team leaders. Effective team leaders are able to vary their leadership style to accommodate the particular context and the needs of their constituencies without going to extremes; but as emphasized by Jung, each individual has a preferred comfort zone that is least stressful and to which an individual will resort during times of added pressure.

Communication Styles

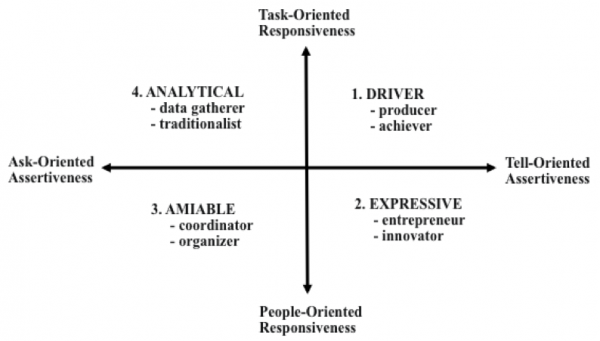

An additional characterization of the Wilson model is the preferred style of communication for different leadership styles, which is illustrated by the dimensions of assertiveness and responsiveness.

Task-oriented assertiveness is exhibited in a communication style that emphasizes the work to be done rather than on the people who will do the work, while the people-oriented communication style addresses personnel issues first and tasks secondly. A tell-oriented communication style involves telling rather than asking, while an ask-oriented assertiveness emphasizes asking over telling. Movies, plays, and novels often include caricatures of extremes in the assertiveness and responsiveness dimensions of Wilson communication styles. An individual’s communication style may fall anywhere within the continuums of assertiveness and responsiveness, from extremes to more moderate styles and may vary considering the situation. Examples include:

- Driver communication style exhibits task-oriented responsiveness and tell-oriented assertiveness.

- Expressive communication style shares tell-oriented assertiveness with the driver style, but favors people-oriented responsiveness.

- Amiable communication style involves asking rather than telling (as does the analytical style) and emphasizes people relationships over task orientation (as does the expressive style).

- Analytical communication style exhibits task-oriented responsiveness and ask-oriented assertiveness.

The most comfortable communication occurs when individuals share the same communication styles or share adjacent quadrants in Figure 1. Difficult communication may occur when individuals are in diagonal quadrants; for example, communication between an extreme amiable style and an extreme driver style. Technical leaders and others can improve communications by being aware of different communication styles (both their own and others) and by modifying their communication style to accommodate the communication styles of others.

Management Responsibilities

Leading a systems engineering team involves communicating, coordinating, providing guidance, and maintaining progress and morale. Managing a project, according to the PMBOK® Guide (PMBOK 2013), involves application of the five process groups of project management: initiating, planning, executing, monitoring and controlling, and closing. Colloquially, systems engineering project/program management is concerned with making and updating plans and estimates, providing resources, collecting and analyzing product and process data, working with the technical leader to control work processes and work products, as well as managing the overall schedule and budget. Good engineering managers are not necessarily good technical leaders and good technical leaders are not necessarily good engineering managers; the expression of different personality traits and skill sets is required. Those who are effective as both managers and leaders have both analytical and interpersonal skills, although their comfort zone may be in one of managing or leading. Two management issues that are typically the responsibility of a systems engineering team leader are:

- Establishing and maintaining the division of responsibility among him or herself, the systems engineering team leader, and the project/program manager.

- Developing, implementing, and maintaining the systems engineering plan (SEP).

Relationships between systems engineering and project management are addressed in the Part 6 Knowledge Area (KA) of the SEBoK, Systems Engineering and Project Management. Also, see the Part 5 KA Enabling Teams for a discussion of the relationships between a project/program manager and a systems engineering technical leader.

The System Engineering Plan (SEP) is, or should be, the highest-level plan for managing the Systems Engineering effort and the technical aspects of a project or program. It defines how a project will be organized and conducted in terms of both performing and controlling the Systems Engineering activities needed to address a project's system requirements and technical content. It can have a number of secondary technical plans that provide details on specific technical areas and supporting processes, procedures, tools. Also, see the Planning article in Part 3, which includes a section on Systems Engineering Planning Process Overview.

In United States DoD acquisition programs, the System Engineering Plan (SEP) is a Government produced document which assists in the development, communication, and management of the overall systems engineering (SE) approach that guides all technical activities of the program. It provides direction to developers for program execution. The developer uses the SEP as guidance for producing the System Engineering Management Plan (SEMP), which is a separate document and usually a contract deliverable that aligns with the SEP. As the SEP is a Government produced and maintained document and the SEMP is a developer/contractor developed and maintained document, the SEMP is typically a standalone, coordinated document.

The following SEP outline from (ODASD 2011) serves as an example (see https://acc.dau.mil/ILC_SEP for a discussion of the outline).

- Introduction – Purpose and Update Plan

- Program Technical Requirements

- Architectures and Interface Control

- Technical Certifications

- Engineering Resources and Management

- Technical Schedule and Schedule Risk Assessment

- Engineering Resources and Cost/Schedule Reporting

- Engineering and Integration Risk Management

- Technical Organization

- Relationships with External Technical Organizations

- Technical Performance Measures and Metrics

- Technical Activities and Products

- Results of Previous Phase SE Activities

- Planned SE Activities for the Next Phase

- Requirements Development and Change Process

- Technical Reviews

- Configuration and Change Management Process

- Design Considerations

- Engineering Tools

- Annex A – Acronyms

SEP templates are often tailored to meet the needs of individual projects or programs by adding needed elements and modifying or deleting other elements. A systems engineering team leader typically works other team members, the project/program manager (or management team), and other stakeholders to develop the SEP and maintain currency of the plan as a project evolves. Some organizations provide one or more SEP templates and offer guidance for developing and maintaining an SEP. Some organizations have a functional group that can provide assistance in developing the SEP.

References

Works Cited

Fairley, R.E. Managing and Leading Software Projects. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470294550.

Hammer, A.L. 2001.Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Work Styles Report. Mountain View, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Available: http://www.cpp.com/images/reports/smp261182.pdf.

Jung, Carl Gustav. 1971.Psychological Type. Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 6. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09774.

Myers, I.B., and P.B. Myers. 1995. Gifts Differing: Understanding Personality Type, 2nd ed. Mountain View, CA: Davies-Black Publishing under special license from CPP, Inc.

Nowack, K. 1996.Is the Myers Briggs Type Indicator the Right Tool to Use? Performance in Practice. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Training and Development (ASTD).

ODASD. 2011. Systems Engineering Plan Outline, version 1.0. Arlington, VA: Office Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (ODASD) Systems Engineering (SE) Division. Available: https://acc.dau.mil/ILC_SEP.

PMI. 2013. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 5th ed. Newtown Square, PA, USA: Project Management Institute (PMI).

Wilson, L. 2004. The Social Styles Handbook. Belgium: Nova Vista Publishing.

Yukl, G. 2013. Leadership in Organizations, 8th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Pearson.

Primary References

Fairley, R.E. 2009. Managing and Leading Software Projects. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

Myers, I.B., and P.B. Myers. 1995. Gifts Differing: Understanding Personality Type, 2nd ed. Mountain View, CA: Davies-Black Publishing under special license from CPP, Inc.

Wilson, Larry. 2004. The Social Styles Handbook. Belgium: Nova Vista Publishing.

Additional References

None.

SEBoK Discussion

Please provide your comments and feedback on the SEBoK below. You will need to log in to DISQUS using an existing account (e.g. Yahoo, Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) or create a DISQUS account. Simply type your comment in the text field below and DISQUS will guide you through the login or registration steps. Feedback will be archived and used for future updates to the SEBoK. If you provided a comment that is no longer listed, that comment has been adjudicated. You can view adjudication for comments submitted prior to SEBoK v. 1.0 at SEBoK Review and Adjudication. Later comments are addressed and changes are summarized in the Letter from the Editor and Acknowledgements and Release History.

If you would like to provide edits on this article, recommend new content, or make comments on the SEBoK as a whole, please see the SEBoK Sandbox.

blog comments powered by Disqus