Measurement

Lead Authors: Garry Roedler, Ray Madachy

Measurement and the accompanying analysis are fundamental elements of systems engineering (SE) and technical management. SE measurement provides information relating to the products developed, services provided, and processes implemented to support effective management of the processes and to objectively evaluate product or service quality. Measurement supports realistic planning, provides insight into actual performance, and facilitates assessment of suitable actions (Roedler and Jones 2005, 1-65; Frenz et al. 2010).

Appropriate measures and indicators are essential inputs to tradeoff analyses to balance cost, schedule, and technical objectives. Periodic analysis of the relationships between measurement results and review of the requirements and attributes of the system provides insights that help to identify issues early, when they can be resolved with less impact. Historical data, together with project or organizational context information, forms the basis for the predictive models and methods that should be used.

Fundamental Concepts

The discussion of measurement in this article is based on some fundamental concepts. Roedler et al. (2005, 1-65) states three key SE measurement concepts that are paraphrased here:

- SE measurement is a consistent but flexible process tailored to the unique information needs and characteristics of a particular project or organization and revised as information needs change.

- Decision makers must understand what is being measured. Key decision-makers must be able to connect what is being measured to what they need to know and what decisions they need to make as part of a closed-loop, feedback control process (Frenz et al. 2010).

- Measurement must be used to be effective.

Measurement Process Overview

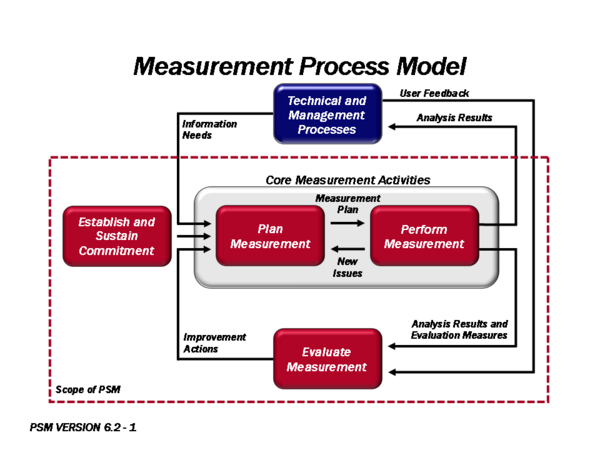

The measurement process as presented here consists of four activities from Practical Software and Systems Measurement (PSM) (2011) and described in (ISO/IEC/IEEE 15939; McGarry et al. 2002):

- establish and sustain commitment

- plan measurement

- perform measurement

- evaluate measurement

This approach has been the basis for establishing a common process across the software and systems engineering communities. This measurement approach has been adopted by the Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) measurement and analysis process area (SEI 2006, 10), as well as by international systems and software engineering standards (ISO/IEC/IEEE 15939; ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288, 1). The International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) Measurement Working Group has also adopted this measurement approach for several of their measurement assets, such as the INCOSE SE Measurement Primer (Frenz et al. 2010) and Technical Measurement Guide (Roedler and Jones 2005). This approach has provided a consistent treatment of measurement that allows the engineering community to communicate more effectively about measurement. The process is illustrated in Figure 1 from Roedler and Jones (2005) and McGarry et al. (2002).

Establish and Sustain Commitment

This activity focuses on establishing the resources, training, and tools to implement a measurement process and ensure that there is a management commitment to use the information that is produced. Refer to PSM (August 18, 2011) and SPC (2011) for additional detail.

Plan Measurement

This activity focuses on defining measures that provide insight into project or organization information needs. This includes identifying what the decision-makers need to know and when they need to know it, relaying these information needs to those entities in a manner that can be measured, and identifying, prioritizing, selecting, and specifying measures based on project and organization processes (Jones 2003, 15-19). This activity also identifies the reporting format, forums, and target audience for the information provided by the measures.

Here are a few widely used approaches to identify the information needs and derive associated measures, where each can be focused on identifying measures that are needed for SE management:

- The PSM approach, which uses a set of information categories, measurable concepts, and candidate measures to aid the user in determining relevant information needs and the characteristics of those needs on which to focus (PSM August 18, 2011).

- The (GQM) approach, which identifies explicit measurement goals. Each goal is decomposed into several questions that help in the selection of measures that address the question and provide insight into the goal achievement (Park, Goethert, and Florac 1996).

- Software Productivity Center’s (SPC's) 8-step Metrics Program, which also includes stating the goals and defining measures needed to gain insight for achieving the goals (SPC 2011).

The following are good sources for candidate measures that address information needs and measurable concepts/questions:

- PSM Web Site (PSM 2011)

- PSM Guide, Version 4.0, Chapters 3 and 5 (PSM 2000)

- SE Leading Indicators Guide, Version 2.0, Section 3 (Roedler et al. 2010)

- Technical Measurement Guide, Version 1.0, Section 10 (Roedler and Jones 2005, 1-65)

- Safety Measurement (PSM White Paper), Version 3.0, Section 3.4 (Murdoch 2006, 60)

- Security Measurement (PSM White Paper), Version 3.0, Section 7 (Murdoch 2006, 67)

- Measuring Systems Interoperability, Section 5 and Appendix C (Kasunic and Anderson 2004)

- Measurement for Process Improvement (PSM Technical Report), version 1.0, Appendix E (Statz 2005)

The INCOSE SE Measurement Primer (Frenz et al. 2010) provides a list of attributes of a good measure with definitions for each attribute; these attributes include relevance, completeness, timeliness, simplicity, cost effectiveness, repeatability, and accuracy. Evaluating candidate measures against these attributes can help assure the selection of more effective measures.

The details of each measure need to be unambiguously defined and documented. Templates for the specification of measures and indicators are available on the PSM website (2011) and in Goethert and Siviy (2004).

Perform Measurement

This activity focuses on the collection and preparation of measurement data, measurement analysis, and the presentation of the results to inform decision makers. The preparation of the measurement data includes verification, normalization, and aggregation of the data, as applicable. Analysis includes estimation, feasibility analysis of plans, and performance analysis of actual data against plans.

The quality of the measurement results is dependent on the collection and preparation of valid, accurate, and unbiased data. Data verification, validation, preparation, and analysis techniques are discussed in PSM (2011) and SEI (2010). Per TL 9000, Quality Management System Guidance, The analysis step should integrate quantitative measurement results and other qualitative project information, in order to provide managers the feedback needed for effective decision making (QuEST Forum 2012, 5-10). This provides richer information that gives the users the broader picture and puts the information in the appropriate context.

There is a significant body of guidance available on good ways to present quantitative information. Edward Tufte has several books focused on the visualization of information, including The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (Tufte 2001).

Other resources that contain further information pertaining to understanding and using measurement results include

- PSM (2011)

- ISO/IEC/IEEE 15939, clauses 4.3.3 and 4.3.4

- Roedler and Jones (2005), sections 6.4, 7.2, and 7.3

Evaluate Measurement

This activity involves the analysis of information that explains the periodic evaluation and improvement of the measurement process and specific measures. One objective is to ensure that the measures continue to align with the business goals and information needs, as well as provide useful insight. This activity should also evaluate the SE measurement activities, resources, and infrastructure to make sure it supports the needs of the project and organization. Refer to PSM (2011) and Practical Software Measurement: Objective Information for Decision Makers (McGarry et al. 2002) for additional detail.

Systems Engineering Leading Indicators

Leading indicators are aimed at providing predictive insight that pertains to an information need. A SE leading indicator is a measure for evaluating the effectiveness of a how a specific activity is applied on a project in a manner that provides information about impacts that are likely to affect the system performance objectives (Roedler et al. 2010). Leading indicators may be individual measures or collections of measures and associated analysis that provide future systems engineering performance insight throughout the life cycle of the system; they support the effective management of systems engineering by providing visibility into expected project performance and potential future states (Roedler et al. 2010).

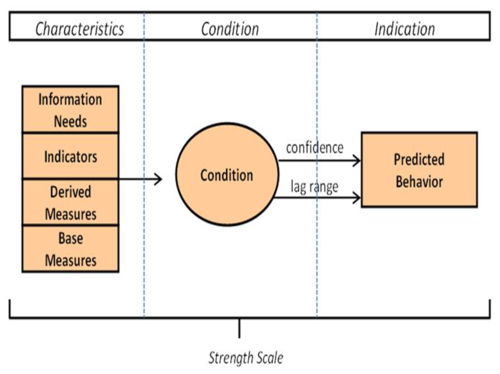

As shown in Figure 2, a leading indicator is composed of characteristics, a condition, and a predicted behavior. The characteristics and conditions are analyzed on a periodic or as-needed basis to predict behavior within a given confidence level and within an accepted time range into the future. More information is also provided by Roedler et al. (2010).

Technical Measurement

Technical measurement is the set of measurement activities used to provide information about progress in the definition and development of the technical solution, ongoing assessment of the associated risks and issues, and the likelihood of meeting the critical objectives of the acquirer. This insight helps an engineer make better decisions throughout the life cycle of a system and increase the probability of delivering a technical solution that meets both the specified requirements and the mission needs. The insight is also used in trade-off decisions when performance is not within the thresholds or goals.

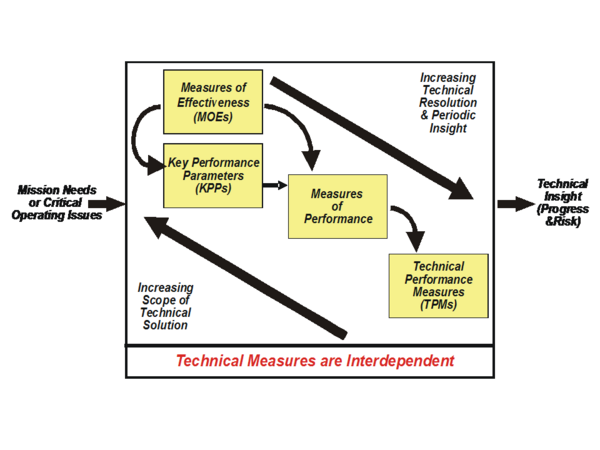

Technical measurement includes measures of effectiveness (MOEs), measures of performance (MOPs), and technical performance measures (TPMs) (Roedler and Jones 2005, 1-65). The relationships between these types of technical measures are shown in Figure 3 and explained in the reference for Figure 3. Using the measurement process described above, technical measurement can be planned early in the life cycle and then performed throughout the life cycle with increasing levels of fidelity as the technical solution is developed, facilitating predictive insight and preventive or corrective actions. More information about technical measurement can be found in the NASA Systems Engineering Handbook, System Analysis, Design, Development: Concepts, Principles, and Practices, and the Systems Engineering Leading Indicators Guide (NASA December 2007, 1-360, Section 6.7.2.2; Wasson 2006, Chapter 34; Roedler and Jones 2005).

Service Measurement

The same measurement activities can be applied for service measurement; however, the context and measures will be different. Service providers have a need to balance efficiency and effectiveness, which may be opposing objectives. Good service measures are outcome-based, focus on elements important to the customer (e.g., service availability, reliability, performance, etc.), and provide timely, forward-looking information.

For services, the terms critical success factors (CSF) and key performance indicators (KPI) are used often when discussing measurement. CSFs are the key elements of the service or service infrastructure that are most important to achieve the business objectives. KPIs are specific values or characteristics measured to assess achievement of those objectives.

More information about service measurement can be found in the Service Design and Continual Service Improvement volumes of BMP (2010, 1). More information on service SE can be found in the Service Systems Engineering article.

Linkages to Other Systems Engineering Management Topics

SE measurement has linkages to other SEM topics. The following are a few key linkages adapted from Roedler and Jones (2005):

- Planning – SE measurement provides the historical data and supports the estimation for, and feasibility analysis of, the plans for realistic planning.

- Assessment and Control – SE measurement provides the objective information needed to perform the assessment and determination of appropriate control actions. The use of leading indicators allows for early assessment and control actions that identify risks and/or provide insight to allow early treatment of risks to minimize potential impacts.

- Risk Management – SE risk management identifies the information needs that can impact project and organizational performance. SE measurement data helps to quantify risks and subsequently provides information about whether risks have been successfully managed.

- Decision Management – SE Measurement results inform decision making by providing objective insight.

Practical Considerations

Key pitfalls and good practices related to SE measurement are described in the next two sections.

Pitfalls

Some of the key pitfalls encountered in planning and performing SE Measurement are provided in Table 1.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Golden Measures |

|

| Single-Pass Perspective |

|

| Unknown Information Need |

|

| Inappropriate Usage |

|

Good Practices

Some good practices gathered from the references are provided in Table 2.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Periodic Review |

|

| Action Driven |

|

| Integration into Project Processes |

|

| Timely Information |

|

| Relevance to Decision Makers |

|

| Data Availability |

|

| Historical Data |

|

| Information Model |

|

Additional information can be found in the Systems Engineering Measurement Primer, Section 4.2 (Frenz et al. 2010), and INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook, Section 5.7.1.5 (2012).

References

Works Cited

Frenz, P., G. Roedler, D.J. Gantzer, P. Baxter. 2010. Systems Engineering Measurement Primer: A Basic Introduction to Measurement Concepts and Use for Systems Engineering. Version 2.0. San Diego, CA: International Council on System Engineering (INCOSE). INCOSE‐TP‐2010‐005‐02. Accessed April 13, 2015 at http://www.incose.org/ProductsPublications/techpublications/PrimerMeasurement.

INCOSE. 2012. Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities, version 3.2.2. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.2.2.

ISO/IEC/IEEE. 2007. Systems and software engineering - Measurement process. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), ISO/IEC/IEEE 15939:2007.

ISO/IEC/IEEE. 2015. Systems and Software Engineering -- System Life Cycle Processes. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organisation for Standardisation / International Electrotechnical Commissions / Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288:2015.

Kasunic, M. and W. Anderson. 2004. Measuring Systems Interoperability: Challenges and Opportunities. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Software Engineering Institute (SEI)/Carnegie Mellon University (CMU).

McGarry, J., D. Card, C. Jones, B. Layman, E. Clark, J. Dean, F. Hall. 2002. Practical Software Measurement: Objective Information for Decision Makers. Boston, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley.

NASA. 2007. Systems Engineering Handbook. Washington, DC, USA: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), December 2007. NASA/SP-2007-6105.

Park, R.E., W.B. Goethert, and W.A. Florac. 1996. Goal-Driven Software Measurement – A Guidebook. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Software Engineering Institute (SEI)/Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), CMU/SEI-96-BH-002.

PSM. 2011. "Practical Software and Systems Measurement." Accessed August 18, 2011. Available at: http://www.psmsc.com/.

PSM. 2000. Practical Software and Systems Measurement (PSM) Guide, version 4.0c. Practical Software and System Measurement Support Center. Available at: http://www.psmsc.com/PSMGuide.asp.

PSM Safety & Security TWG. 2006. Safety Measurement, version 3.0. Practical Software and Systems Measurement. Available at: http://www.psmsc.com/Downloads/TechnologyPapers/SafetyWhitePaper_v3.0.pdf.

PSM Safety & Security TWG. 2006. Security Measurement, version 3.0. Practical Software and Systems Measurement. Available at: http://www.psmsc.com/Downloads/TechnologyPapers/SecurityWhitePaper_v3.0.pdf.

QuEST Forum. 2012. Quality Management System (QMS) Measurements Handbook, Release 5.0. Plano, TX, USA: Quest Forum.

Roedler, G., D. Rhodes, C. Jones, and H. Schimmoller. 2010. Systems Engineering Leading Indicators Guide, version 2.0. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2005-001-03.

Roedler, G. and C. Jones. 2005. Technical Measurement Guide, version 1.0. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2003-020-01.

SEI. 2010. "Measurement and Analysis Process Area" in Capability Maturity Model Integrated (CMMI) for Development, version 1.3. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Software Engineering Institute (SEI)/Carnegie Mellon University (CMU).

Software Productivity Center, Inc. 2011. Software Productivity Center web site. August 20, 2011. Available at: http://www.spc.ca/.

Statz, J. et al. 2005. Measurement for Process Improvement, version 1.0. York, UK: Practical Software and Systems Measurement (PSM).

Tufte, E. 2006. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire, CT, USA: Graphics Press.

Wasson, C. 2005. System Analysis, Design, Development: Concepts, Principles, and Practices. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley and Sons.

Primary References

Frenz, P., G. Roedler, D.J. Gantzer, P. Baxter. 2010. Systems Engineering Measurement Primer: A Basic Introduction to Measurement Concepts and Use for Systems Engineering. Version 2.0. San Diego, CA: International Council on System Engineering (INCOSE). INCOSE‐TP‐2010‐005‐02. Accessed April 13, 2015 at http://www.incose.org/ProductsPublications/techpublications/PrimerMeasurement.

ISO/IEC/IEEE. 2007. Systems and Software Engineering - Measurement Process. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), ISO/IEC/IEEE 15939:2007.

PSM. 2000. Practical Software and Systems Measurement (PSM) Guide, version 4.0c. Practical Software and System Measurement Support Center. Available at: http://www.psmsc.com.

Roedler, G., D. Rhodes, C. Jones, and H. Schimmoller. 2010. Systems Engineering Leading Indicators Guide, version 2.0. San Diego, CA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2005-001-03.

Roedler, G. and C. Jones. 2005. Technical Measurement Guide, version 1.0. San Diego, CA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2003-020-01.

Additional References

Kasunic, M. and W. Anderson. 2004. Measuring Systems Interoperability: Challenges and Opportunities. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Software Engineering Institute (SEI)/Carnegie Mellon University (CMU).

McGarry, J. et al. 2002. Practical Software Measurement: Objective Information for Decision Makers. Boston, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley.

NASA. 2007. NASA Systems Engineering Handbook. Washington, DC, USA: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), December 2007. NASA/SP-2007-6105.

Park, Goethert, and Florac. 1996. Goal-Driven Software Measurement – A Guidebook. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Software Engineering Institute (SEI)/Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), CMU/SEI-96-BH-002.

PSM. 2011. "Practical Software and Systems Measurement." Accessed August 18, 2011. Available at: http://www.psmsc.com/.

PSM Safety & Security TWG. 2006. Safety Measurement, version 3.0. Practical Software and Systems Measurement. Available at: http://www.psmsc.com/Downloads/TechnologyPapers/SafetyWhitePaper_v3.0.pdf.

PSM Safety & Security TWG. 2006. Security Measurement, version 3.0. Practical Software and Systems Measurement. Available at: http://www.psmsc.com/Downloads/TechnologyPapers/SecurityWhitePaper_v3.0.pdf.

SEI. 2010. "Measurement and Analysis Process Area" in Capability Maturity Model Integrated (CMMI) for Development, version 1.3. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Software Engineering Institute (SEI)/Carnegie Mellon University (CMU).

Software Productivity Center, Inc. 2011. Software Productivity Center web site. August 20, 2011. Available at: http://www.spc.ca/.

Statz, J. 2005. Measurement for Process Improvement, version 1.0. York, UK: Practical Software and Systems Measurement (PSM).

Tufte, E. 2006. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire, CT, USA: Graphics Press.

Wasson, C. 2005. System Analysis, Design, Development: Concepts, Principles, and Practices. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley and Sons.