Applying Life Cycle Processes

Lead Author: Rick Adcock

The Generic Life Cycle Model describes a set of life cycle stages and their relationships. In defining this we described some of the technical and management activities critical to the success of each stage. While this association of activity to stage is important, we must also recognize the through life relationships between these activities to ensure we take a systems approach.

Systems Engineering technical and management activities are defined in a set of life cycle processes. These group together closely related activities and allow us to describe the relationships between them. In this topic, we discuss a number of views on the nature of the inter-relationships between process activities within a life cycle model.

In general, the technical and management activities are applied in accordance with the principles of concurrency, iteration and recursion described in the generic systems engineering paradigm. These principles overlap to some extent and can be seen as related views of the same fundamental need to ensure we can take a holistic systems approach, while allowing for some structuring and sequence of our activities. The views presented below should be seen as examples of the ways in which different SE authors present these overlapping ideas.

Life Cycle Process Terminology

Process

A process is a series of actions or steps taken in order to achieve a particular end. Processes can be performed by humans or machines transforming inputs into outputs.

In the SEBoK, processes are interpreted in several ways, including: technical, life cycle, business, or manufacturing flow processes. Many of the Part 3 sections are structured along technical processes (e.g. design, verification); however, Life Cycle Models also describes a number of high-level program life cycle sequence which call themselves processes (e.g. rational unified process (RUP), etc.).

Part 4: Applications of Systems Engineering and Part 5: Enabling Systems Engineering utilize processes that are related to services and business enterprise operations.

Systems Engineering life cycle processes define technical and management activities performed across one or more stages to provide the information needed to make life cycle decisions; and to enable realization, use and sustainment of a system-of-interest (SoI) across its life cycle model as necessary. This relationship between life cycle models and process activities can be used to describe how SE is applied to different system contexts.

Requirement

A requirement is something that is needed or wanted but may not be compulsory in all circumstances. Requirements may refer to product or process characteristics or constraints. Different understandings of requirements are dependent upon process state, level of abstraction, and type (e.g. functional, performance, constraint). An individual requirement may also have multiple interpretations over time.

Requirements exist at multiple levels of enterprise or systems with multiple levels of abstraction. This ranges from the highest level of the enterprise capability or customer need to the lowest level of the system design. Thus, requirements need to be defined at the appropriate level of detail for the level of the entity to which they apply. See the articles System Concept Definition and System Requirements Definition for further detail on the transformation of needs and requirements from the enterprise to the lowest system element across concept definition and system definition.

Architecture

An architecture refers to the organizational structure of a system, whereby the system can be defined in different contexts. Architecting is the art or practice of designing the structures. See below for further discussions on the use of levels of Logical and Physical architecture models to define related system and system elements; and support the requirements activities.

Architectures can apply for a system product, enterprise, or service. For example, Part 3 mostly considers product or service related architectures that systems engineers create, but enterprise architecture describes the structure of an organization. Part 5: Enabling Systems Engineering interprets enterprise architecture in a much broader manner than an IT system used across an organization, which is a specific instance of architecture.

Frameworks are closely related to architectures, as they are ways of representing architectures. See Architecture Framework for definition and examples.

Other Processes

A number of other life cycle processes are mentioned below, including system analysis, integration, verification, validation, deployment, operation, maintenance and disposal; they are discussed in detail in the System Realization and System Deployment and Use knowledge areas.

Life Cycle Process Concurrency

In the Generic Life Cycle Model, we have listed key activities critical to successful completion of each stage. This is a useful way to illustrate the goals of each stage and gives an indication of how processes align with these stages. This can be important when considering how to plan for resources, milestones, etc. However, it is important to observe that the execution of process activities is not compartmentalized to particular life cycle stages (Lawson 2010).

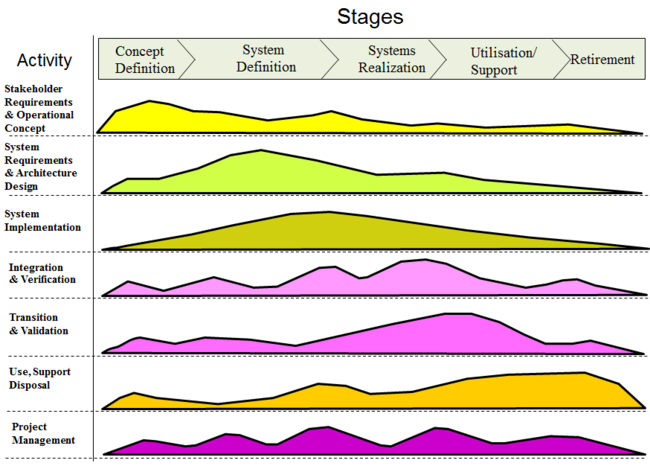

Figure 1 shows a simple illustration of the through life nature of technical and management processes. This figure builds directly on the "hump diagram" principles described in Systems Approach Applied to Engineered Systems.

The lines on this diagram represent the amount of activity for each process over the generic life cycle. The peaks (or humps) of activity represent the periods when a process activity becomes the main focus of a stage. The activity before and after these peaks may represent through life issues raised by a process focus, e.g. how likely maintenance constraints will be represented in the system requirements. These considerations help maintain a more holistic perspective in each stage, or they can represent forward planning to ensure the resources needed to complete future activities have been included in estimates and plans, e.g. all resources needed for verification are in place or available. Ensuring this hump diagram principle is implemented in a way which is achievable, affordable and appropriate to the situation is a critical driver for all life cycle models.

Life Cycle Process Iteration

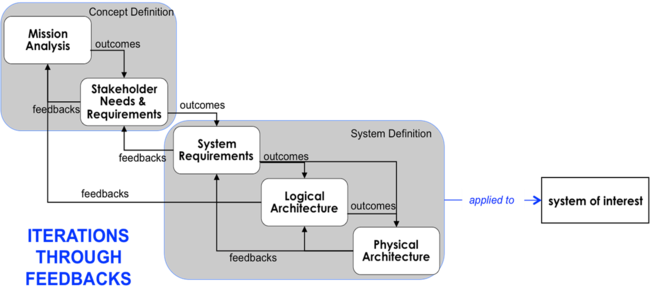

The concept of iteration applies to life cycle stages within a life cycle model, and also applies to processes. Figure 2 below gives an example of iteration in the life cycle processes associated with concept and system definition.

There is generally a close coupling between the exploration of a problem or opportunity and the definition of one or more feasible solutions; see Systems Approach to Engineered Systems. Thus, the related processes in this example will normally be applied in an iterative way. The relationships between these processes are further discussed in the System Definition KA.

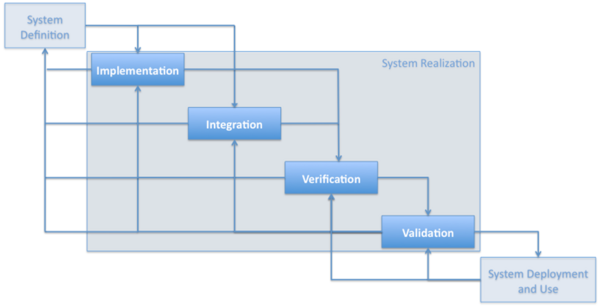

Figure 3 below gives an example of the iteration between the other life cycle processes.

The iterations in this example relate to the overlaps in process outcomes shown in Figure 1. They either allow consideration of cross process issues to influence the system definition (e.g. considering likely integration or verification approaches might make us think about failure modes or add data collection or monitoring elements into the system) or they allow risk management and through life planning activities to identify the need for future activities.

The relationships between these processes are further discussed in system realization and system deployment and use.

Life Cycle Process Recursion

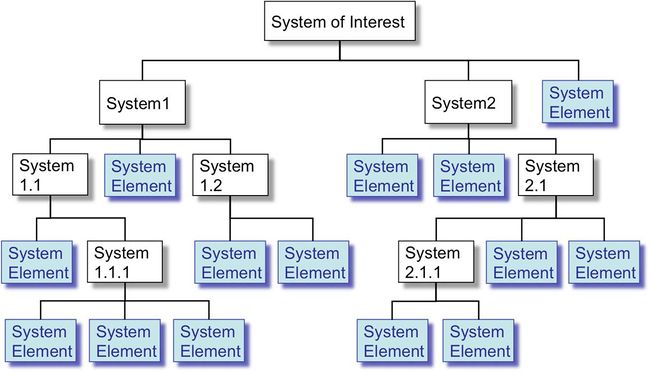

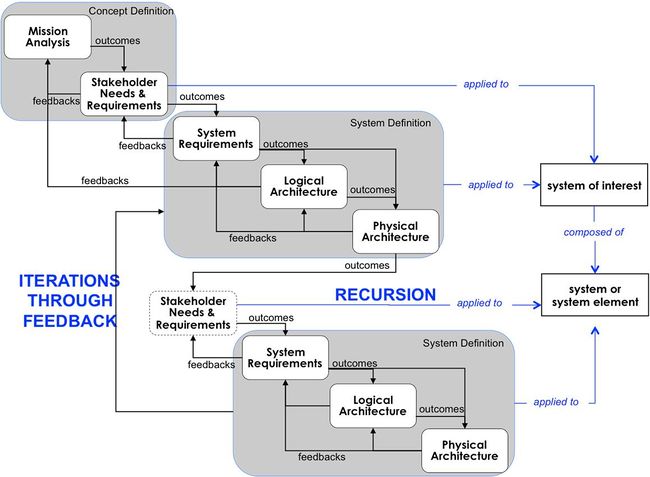

The comprehensive definition of a SoI is generally achieved using decomposition layers and system elements. Figure 4 presents a fundamental schema of a system breakdown structure.

In each decomposition layer and for each system, the System Definition processes are applied recursively because the notion of "system" is in itself recursive; the notions of SoI, system, and system element are based on the same concepts (see Part 2). Figure 5 shows an example of the recursion of life cycle processes.

Systems Approach to Solution Synthesis

The sections above give different perspectives on how SE life cycle processes are related and how this shapes their application. Solution synthesis is described in Part 2 as a way of taking a systems approach to creating solutions. Synthesis is, in general, a mixture of top-down and bottom-up approaches as discussed below.

Top-Down Approach: From Problem to Solution

In a top-down approach, concept definition activities are focused primarily on understanding the problem, the operational needs/requirements within the problem space, and the conditions that constrain the solution and bound the solution space. The concept definition activities determine the mission context, mission analysis, and the needs to be fulfilled in that context by a new or modified system (i.e. the SoI), and address stakeholder needs and requirements.

The system definition activities consider functional, behavioral, temporal, and physical aspects of one or more solutions based on the results of concept definition. System analysis considers the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed system solutions both in terms of how they satisfy the needs established in concept definition, as well as the relative cost, time scales and other development issues. This may require further refinement of the concept definition to ensure all legacy relationships and stakeholders relevant to a particular solution architecture have been considered in the stakeholder requirements.

The outcomes of this iteration between Concept Definition and System Definition define a required system solution and its associated problem context, which are used for System Realization, System Deployment and Use, and Product and Service Life Management of one or more solution implementations. In this approach, problem understanding and solution selection activities are completed in the front-end portion of system development and design and then maintained and refined as necessary throughout the life cycle of any resulting solution systems. Top-down activities can be sequential, iterative, recursive or evolutionary depending upon the life cycle model.

Bottom-Up Approach: Evolution of the Solution

In some situations, the concept definition activities determine the need to evolve existing capabilities or add new capabilities to an existing system. During the concept definition, the alternatives to address the needs are evaluated. Engineers are then led to reconsider the system definition in order to modify or adapt some structural, functional, behavioral, or temporal properties during the product or service life cycle for a changing context of use or for the purpose of improving existing solutions.

Reverse engineering is often necessary to enable system engineers to (re)characterize the properties of the system-of-interest (SoI) or its elements. This is an important step to ensure that system engineers understand the SoI before beginning modification. For more information on system definition, see the System Definition article.

A bottom-up approach is necessary for analysis purposes, or for (re)using existing elements in the design architecture. Changes in the context of use or a need for improvement can prompt this. In contrast, a top-down approach is generally used to define an initial design solution corresponding to a problem or a set of needs.

Solution Synthesis

In most real problems, a combination of bottom-up and top-down approaches provides the right mixture of innovative solution thinking driven by need, and constrained and pragmatic thinking driven by what already exists. This is often referred to as a “middle-out” approach.

As well as being the most pragmatic approach, synthesis has the potential to keep the life cycle focused on whole system issues, while allowing the exploration of the focused levels of detail needed to describe realizable solutions; see Synthesising System Solutions for more information.

References

Works Cited

Faisandier, A. 2012. Systems Architecture and Design. Belberaud, France: Sinergy'Com.

Lawson, H. 2010. A Journey Through the Systems Landscape. London, UK: College Publications.

Primary References

INCOSE. 2015. Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities, version 4.0. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc, ISBN: 978-1-118-99940-0.

Additional References

None.