Difference between revisions of "Related Business Activities"

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

*Portfolio Management | *Portfolio Management | ||

*Resource Allocation & Budgeting | *Resource Allocation & Budgeting | ||

| − | *Program & [[Project (glossary)|Project]] Management | + | *[[Program (glossary)| Program]] & [[Project (glossary)|Project]] Management |

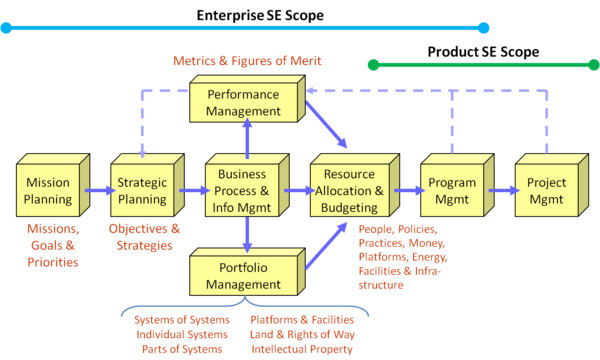

The figure below shows how these business activities relate to each other as well as the relative scope of ESE and product SE (Martin 2010). | The figure below shows how these business activities relate to each other as well as the relative scope of ESE and product SE (Martin 2010). | ||

Revision as of 14:54, 7 September 2011

The following business management activities can be supported by enterprise systems engineering (ese) (ESE) activities:

- Mission & Strategic Planning

- Business Processes & Information Management

- Performance Management

- Portfolio Management

- Resource Allocation & Budgeting

- Program & Project Management

The figure below shows how these business activities relate to each other as well as the relative scope of ESE and product SE (Martin 2010).

Figure 1. Related Business Activities (Source: (Martin 2010), Used with Permission)

Shown in this manner, these business activities can be considered to be separate processes with a clear precedence in terms of which process drives other processes. Traditional Systems Engineering (TSE) uses “requirements” to specify the essential features and functions of a system. An enterprise , on the other hand, typically uses goals and objectives to specify the fundamental characteristics of desired enterprise operational capabilities. The enterprise objectives and strategies are used in portfolio management to discriminate between options and to select the appropriate balanced portfolio of systems and other enterprise resources.

The first three activities listed above are covered in Enabling Businesses and Enterprises to Perform Systems Engineering. The other business management activities are described in more detail below in how they relate to ESE.

Business Management Cycles

PDCA stands for plan-do-check-act and is a commonly used iterative management process as seen in the figure below. It is also known as the Deming circle or the Shewhart cycle after its two key proponents (Deming 1986; Shewhart 1939). ESE inherently uses the PDCA cycle as one it fundamental tenets. After ESE develops the enterprise transformation plan, the planned improvements are monitored (i.e., “checked” in the PDCA cycle) to ensure they achieve the targeted performance levels. If not, then action needs to be taken (i.e., “act” in the PDCA cycle) to correct the situation and replanning may be required. It is also worth mentioning the utility of using Boyd's OODA loop (observe, orient, decide and act) to augment PDCA. This could be accomplished by first using the OODA loop (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OODA_loop), which is continuous in situation awareness, and then followed by using the PDCA approach, which is discrete, having goals, resources, usually time limits, etc. (Lawson 2010)

Figure 2. PDCA Cycle (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PDCA. Accessed July 2010. Diagram by Karn G. Bulsuk (http://blog.bulsuk.com), Used with Permission)

Portfolio Management

Program and Project Managers direct their activities as they relate to the systems under their control. Enterprise management, on the other hand, means directing the portfolio of items that are necessary to achieving the enterprise goals and objectives. The enterprise may not actually own these portfolio items. They could rent or lease these items, or they could have permission to use them through licensing or assignment.

The enterprise may only need part of a system (e.g., one bank of switching circuits in a system) or may need an entire system of systems (sos) SoS (e.g., switching systems, distribution systems, billing systems, provisioning systems, etc.). Notice that the portfolio items are not just those items related to the systems that systems engineering SE deals with. These could also include platforms (like ships and oil drilling derricks), facilities (like warehouses and airports), land and rights of way (like railroad property easements and municipal covenants), and intellectual property (like patents and trademarks).

The investment community has been using portfolio management for a long time to manage a set of investments to maximize return for a given level of acceptable risk. These techniques have also been applied to a portfolio of “projects” within the enterprise (Kaplan 2009). However, it should be noted that an enterprise is not merely a portfolio of projects. The enterprise portfolio consists of whatever systems, organizations, facilities, intellectual property, and other resources that help it achieve its goals and objectives.

Resource Allocation and Budgeting

The resource allocation activity is driven by the portfolio management definition of the optimal set of portfolio elements. capability gaps are mapped to the elements of the portfolio, and resources are assigned to programs (or other organizational elements) based on the criticality of these gaps. Resources come in the form of people and facilities, policies and practices, money and energy, and platforms and infrastructure. Allocation of resources could also involve the distribution or assignment of corporate assets like communication bandwidth, manufacturing floor space, computing power, intellectual property licenses, and so on. Resource allocation and budgeting is typically done on an annual basis, but more agile enterprises will make this a more continuous process. Some of the resource allocation decisions deal with base operational organizations that are not project related.

Program and Project Management

Within the enterprise, TSE is typically applied inside a Project to engineer a single system (or perhaps a small number of related systems). If there is a SoS or a large, complex individual system to be engineered then this might be handled at the Program level, but is sometimes handled at the Project level, depending on the size and complexity of the system of interest.

There are commonly three basic types of projects in an enterprise. A development project takes a conceptual notion of a system and turns this into a realizable design. A production project takes the realizable design for a system and turns this into physical copies (or instantiations). An operations “project” directly operates each system or supports the operation by others. (Base operations are sometimes called "line organizations" and are not typically called projects per se, but should nonetheless be considered as key elements to be considered when adjusting the enterprise portfolio.) The operations project can also be involved in maintaining the system or supporting maintenance by others. A program can have all three types of projects active simultaneously for the same system, as in this example:

- Project A is developing System X version 3.

- Project B is operating and maintaining System X version 2.

- Project C is maintaining System X version 1 in a warehouse as backup in case of emergencies.

Project management uses TSE as a tool to ensure a well-structured project and to help identify and mitigate cost, schedule, and technical risks involved with system development and implementation. The project level is where the TSE process is most often employed (Martin 1997; ISO/IEC 15288 2008; Wasson 2006; INCOSE 2010; Blanchard and Fabrycky 2010).

Multi-Level Enterprises

An enterprise does not always have full control over the ESE processes. In some cases, an enterprise may have no direct control over the resources necessary to make programs and projects successful. For example, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) is responsible for the “smooth operation of the Internet,” yet it controls none of the requisite resources.

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) is a large open international community of network designers, operators, vendors, and researchers concerned with the evolution of the Internet architecture and the smooth operation of the Internet. … The actual technical work of the IETF is done in its working groups, which are organized by topic into several areas (e.g., routing, transport, security, etc.). Much of the work is handled via mailing lists. The IETF holds meetings three times per year (IETF 2010a).

The IETF has “influence” over these resources even though it does not have direct control:

The IETF is unusual in that it exists as a collection of happenings, but is not a corporation and has no board of directors, no members, and no dues (IETF 2010b).

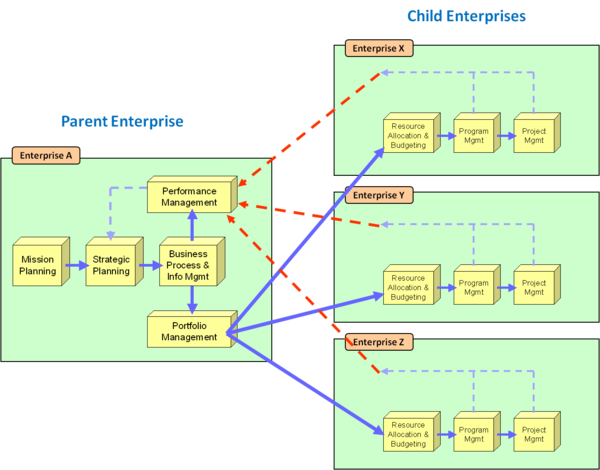

The ESE processes might be allocated between a “parent” enterprise and “children” enterprises, as shown in the figure below (Martin 2010). The parent enterprise, in this case, has no resources. These resources are owned by the subordinate child enterprises. Therefore the parent enterprise does not implement the processes of Resource Allocation and Budgeting, Program Management, and Project Management.

The parent enterprise may have an explicit contract with the subordinate enterprises, or, as in some cases, there is merely a “working relationship” without benefit of legal obligations. The parent enterprise will expect performance feedback from the lower level to ensure that it can meet its own objectives. Where the feedback indicates a deviation from the plan, the objectives can be adjusted or the portfolio is modified to compensate.

Figure 3. Parent and Child Enterprise Relationships (Source: (Martin 2010), Used with Permission)

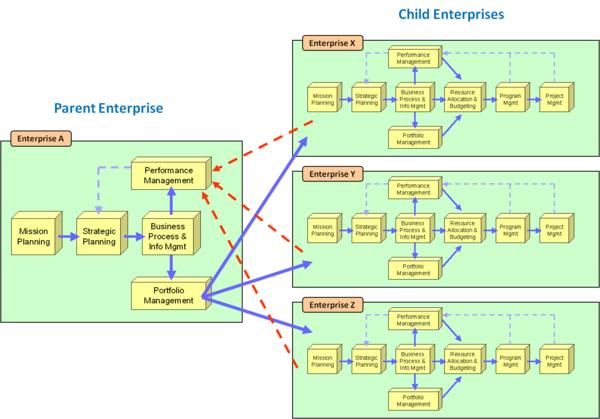

Enterprises X, Y, and Z in the situation shown above will cooperate with each other to the extent that they honor the direction and guidance from the parent enterprise. These enterprises may not even be aware of each other, and, in this case, would be unwittingly cooperating with each other. The situation becomes more complex if each enterprise has its own set of strategic goals and objectives as shown in the figure below.

Figure 4. Mission and Strategic Planning at All Levels of Cooperating Enterprises (Source: (Martin 2010), Used with Permission)

These separate sub-enterprise objectives will sometimes conflict with the objectives of the parent enterprise. Furthermore, each subordinate enterprise has its own strategic objectives that might conflict with those of its siblings. The situation shown here is not uncommon, and illustrates an enterprise of enterprises, so to speak. This highlights the need for application of SE at the enterprise level to handle the complex interactions and understand the overall behavior of the enterprise as a whole. TSE practices can be used, to a certain extent, but these need to be expanded to incorporate additional tools and techniques.

References

Citations

- Blanchard, B. S., and W. J. Fabrycky. 2010. Systems engineering and analysis. Prentice-hall international series in industrial and systems engineering. 5th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall.

- Deming, W. E. 1986. Out of the crisis. MIT Center for Advance Engineering Study.

- IETF. 2010a. Overview of the IETF. in Internet Engineering Task Force, Internet Society (ISOC) [database online]. 2010a Available from http://www.ietf.org/overview.html (accessed 2010).

- ———. 2010b. The Tao of IETF: A Novice’s Guide to the Internet Engineering Task Force (draft-hoffman-tao4677bix-10). in Internet Engineering Task Force, Internet Society (ISOC) [database online]. http://www.ietf.org/tao.html#intro (accessed 2010).

- INCOSE. 2010. INCOSE systems engineering handbook, version 3.2. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.2.

- ISO/IEC 15288. 2008. Systems and software engineering - system life cycle processes. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), ISO/IEC 15288:2008 (E).

- Kaplan, J. 2009. Strategic IT portfolio management: Governing enterprise transformation. Washington, DC: Jeffrey Kaplan PRTM.

- Lawson, H. 2010. A Journey Through the Systems Landscape. College Publications, Kings College, UK.

- Martin, J. N. 2010. An enterprise systems engineering framework. Paper presented at 20th Anniversary International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) International Symposium, 12-15 July, 2010, Chicago, IL, USA.

- ———. 1997. Systems engineering guidebook: A process for developing systems and products. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press.

- Shewhart, W. A. 1939. Statistical method from the viewpoint of quality control. New York: Dover.

- Wasson, C. S. 2006. System analysis, design and development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

Primary References

Martin, J. N. 2010. An Enterprise Systems Engineering Framework. Paper presented at 20th Anniversary International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) International Symposium, 12-15 July, 2010, Chicago, IL, USA.

Additional References

- Arnold, S., and H. Lawson. 2004. Viewing systems from a business management perspective. Systems Engineering, the Journal of the International Council on Systems Engineering 7 (3): 229.

- Beimans, F. P. M., M. M. Lankhorst, W. B. Teeuw, and R. G. van de Wetering. 2001. Dealing with the complexity of business systems architecting. Systems Engineering, the Journal of the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) 4 (2): 118-33.

- Drucker, P. F. 1994. The theory of business. Harvard Business Review (September/October 1994): 95-104.

- Haeckel, S. H. 2003. Leading on demand businesses–Executives as architects. IBM Systems Journal 42 (3): 405-13.

- Kaplan, R., and D. Norton. 1996. The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Lissack, M. R. 2000. Complexity metaphors and the management of a knowledge based enterprise: An exploration of discovery. PhD in Business Administration., Henley Management College.

- Rechtin, E. 1999. Systems architecting of organizations: Why eagles can't swim. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press.

Article Discussion

Signatures

--Blawson 20:43, 15 August 2011 (UTC)