Difference between revisions of "Systems Engineering Overview"

m (Text replacement - "'''SEBoK v. 2.2, released 15 May 2020'''" to "'''SEBoK v. 2.3, released 30 October 2020'''") |

|||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

<center>[[Introduction to Systems Engineering |< Previous Article]] | [[Introduction to Systems Engineering |Parent Article]] | [[Economic Value of Systems Engineering|Next Article >]]</center> | <center>[[Introduction to Systems Engineering |< Previous Article]] | [[Introduction to Systems Engineering |Parent Article]] | [[Economic Value of Systems Engineering|Next Article >]]</center> | ||

| − | <center>'''SEBoK v. 2. | + | <center>'''SEBoK v. 2.4, released 19 May 2021'''</center> |

[[Category:Part 1]] | [[Category:Part 1]] | ||

[[Category:Introduction to Systems Engineering]] | [[Category:Introduction to Systems Engineering]] | ||

Revision as of 19:38, 19 May 2021

Systems engineering (SE) is a transdisciplinary approach and means to enable the realization of successful systems. Successful systems must satisfy the needs of their customers, users and other stakeholders. This article provides an overview of SE as discussed in the SEBoK and the relationship between SE and systems (for additional information on this, please see Part 2).

Systems and Systems Engineering

In the broad community, the term “system” may mean a collection of technical, natural or social elements, or a combination of all three. This may produce ambiguities at times: for example, does “management” refer to management of the SE process, or management of the system being engineered? As with many special disciplines, SE uses terms in ways that may be unfamiliar outside the discipline. For example, in systems science and therefore SE, “open” means that a system is able to interact with its environment--as opposed to being "closed” to its environment. However, in the broader engineering world we would read “open” to mean “non-proprietary” or “publicly agreed upon.” In such cases, the SEBoK tries to avoid misinterpretation by elaborating the alternatives e.g. “system management” or “systems engineering management”.

The SEBoK seeks to position SE within the broader scope of knowledge which considers systems as part of its foundations. To do this without attempting to re-define general systems terminology, SEBoK introduces two related definitions specific to SE:

- An engineered system is a technical or socio-technicalsystem which is the subject of an SE life cycle. It is a system designed or adapted to interact with an anticipated operational environment to achieve one or more intended purposes while complying with applicable constraints.

- An engineered system context centers around an engineered system but also includes in its relationships other engineered, social or natural systems in one or more defined environments.

Since the province of SE is engineered systems, most SE literature assumes this in its terminology. Thus, in an SE discussion, “system architecture” would refer to the architecture of the system being engineered (e.g., a spacecraft) and not the architecture of a natural system outside its boundary (e.g., the solar system). In fact, a spacecraft architecture would cover the wider system context including external factors such as changes in gravity and external air pressure and how these affect the spacecraft's technical and human elements. Thus, the term "system architecture" more properly refers to the engineered system context. The SEBoK tries to be more explicit about this, but may still make these kinds of assumptions when referring directly to other SE literature.

An extensive glossary of terms identifies how terms are used in the SEBoK and shows how their meanings may vary in different contexts. As needed, the glossary includes pointers to articles providing more detail.

For more about the definition of systems, see the article What is a System? in Part 2. The primary focus of SEBoK Part 3: Systems Engineering and Management and Part 4: Applications of Systems Engineering is on how to create or change an engineered system to fulfill the goals of stakeholders within these wider system contexts. The knowledge in Part 5: Enabling Systems Engineering and Part 6: Systems Engineering and Other Disciplines examines the need for SE itself to be integrated and supported within the human activity systems in which it is performed, and the relationships between SE and other engineering and management disciplines.

Scope of Systems Engineering within the Engineered Systems Domain

The scope of SE does not include everything involved in the engineering and management of an engineered system. Activities can be part of the SE environment, but other than the specific management of the SE function, are not considered to be part of SE. Examples include system construction, manufacturing, funding, and general management. This is reflected in the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) top-level definition of systems engineering as, “A transdisciplinary and integrative approach to enable the successful realization, use, and retirement of engineered systems, using systems principles and concepts, and scientific, technological, and management methods” (Fellows 2019). Although SE can enable the realization of a successful system, if an activity that is outside the scope of SE, such as manufacturing, is poorly managed and executed, SE cannot ensure a successful realization.

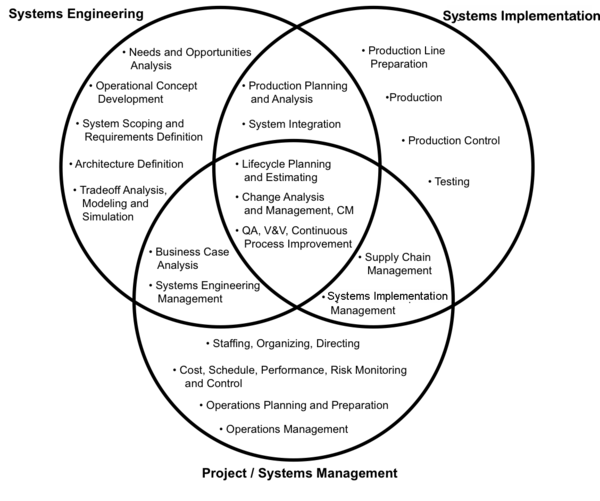

A convenient way to define the scope of SE within engineering and management is to develop a Venn diagram. Figure 3 shows the relationship between SE, system implementation, and project/systems management. Activities, such as analyzing alternative methods for production, testing, and operations, are part of SE planning and analysis functions. Such activities as production line equipment ordering and installation, and its use in manufacturing, while still important SE environment considerations, stand outside the SE boundary. Note that as defined in Figure 3, system implementation engineering also includes the software production aspects of system implementation. Software engineering, then, is not considered a subset of SE.

Traditional definitions of SE have emphasized sequential performance of SE activities, e.g., “documenting requirements, then proceeding with design synthesis …” (INCOSE 2012).Originally, the SEBoK authors & editors departed from tradition to emphasize the inevitable intertwining of system requirements definition and system design in the following revised definition of SE:

Systems Engineering (SE) is an interdisciplinary approach and means to enable the realization of successful systems. It focuses on holistically and concurrently understanding stakeholder needs; exploring opportunities; documenting requirements; and synthesizing, verifying, validating, and evolving solutions while considering the complete problem, from system concept exploration through system disposal. (INCOSE 2012, modified.)

More recently, the INCOSE Fellows have offered an updated definition of SE that has been adopted as the official INCOSE definition:

A transdisciplinary and integrative approach to enable the successful realization, use, and retirement of engineered systems, using systems principles and concepts, and scientific, technological, and management methods.

Part 3: Systems Engineering and Management elaborates on the definition above to flesh out the scope of SE more fully.

Systems Engineering and Engineered Systems Project Life Cycle Context

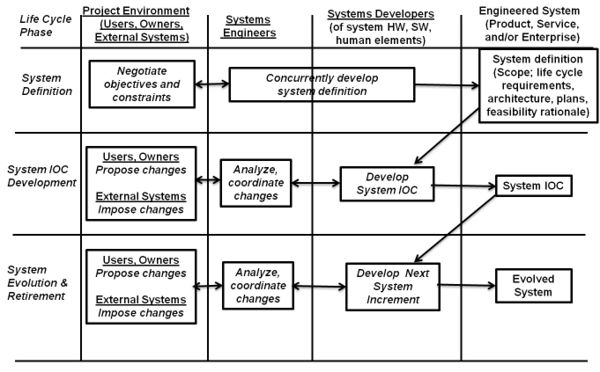

SE is performed as part of a life cycle approach. Figure 2 summarizes the main agents, activities, and artifacts involved in the life cycle of SE, in the context of a project to create and evolve an engineered system.

For each primary project life cycle phase, we see activities being performed by primary agents, changing the state of the ES.

- Primary project life cycle phases appear in the leftmost column. They are system definition, system initial operational capability (IOC) development, and system evolution and retirement.

- Primary agents appear in the three inner columns of the top row. They are systems engineers, systems developers, and primary project-external bodies (users, owners, external systems) which constitute the project environment.

- The ES, which appears in the rightmost column, may be a product, a service, and/or an enterprise.

In each row:

- boxes in each inner column show activities being performed by the agent listed in the top row of that column

- the resulting artifacts appear in the rightmost box.

Arrows indicate dependencies: an arrow from box A to box B means that the successful outcome of box B depends on the successful outcome of box A. Two-headed arrows indicate two-way dependencies: an arrow that points both from box A to box B and from box B to box A means that the successful outcome of each box depends on the successful outcome of the other.

For example, consider how the inevitable changes that arise during system development and evolution are handled:

- One box shows that the system’s users and owners may propose changes.

- The changes must be negotiated with the systems developers, who are shown in a second box.

- The negotiations are mediated by systems engineers, who are shown in a third box in between the first two.

- Since the proposed changes run from left to right and the counter-proposals run from right to left, all three boxes are connected by two-headed arrows. This reflects the two-way dependencies of the negotiation.

An agent-activity-artifact diagram like Figure 1 can be used to capture complex interactions. Taking a more detailed view of the present example demonstrates that:

- The system’s users and owners (stakeholders) propose changes to respond to competitive threats or opportunities, or to adapt to changes imposed by independently evolving external systems, such as Commercial-off-the-Shelf (COTS) products, cloud services, or supply chain enablers.

- Negotiation among these stakeholders and the system developers follows, mediated by the SEs.

- The role of the SEs is to analyze the relative costs and benefits of alternative change proposals and synthesize mutually satisfactory solutions.

References

Works Cited

Checkland, P. 1981. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley.

INCOSE. 2012. Systems Engineering Handbook, version 3.2.2. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE). INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.2.

Fellows. 2019. INCOSE Fellows Briefing to INCOSE Board of Directors. January 2019.

Rechtin, E. 1991. Systems Architecting. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall.

Primary References

INCOSE. 2012. Systems Engineering Handbook, version 3.2.2. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE). INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.2.

Additional References

None.