Enterprise Systems Engineering

6.1 Introduction (3.1)

NOTE: The 6.1 and 3.1 numbering above and likewise below are for tracking purposes and will be deleted in the final version to be released.

This Knowledge Area includes the following Topics:

- Enterprise Systems Engineering Background

- The Enterprise as a System

- Related Business Management Activities

- Enterprise Systems Engineering Key Concepts

- Enterprise Systems Engineering Process Activities

- Enterprise Capability Management

Here are the sections of this top-level article, which provides an introduction to the discipline of Enterprise Systems Engineering (ESE):

6.1.1

Purpose

This article and its subarticles (listed as "Topics" above) provides an introduction to systems engineering (SE) at the enterprise level in contrast to “traditional” SE (TSE) (sometimes called “conventional” or “classical” SE) performed in a development project or to “product” engineering (often called product development in the literature).

The concept of enterprise was instrumental in the great expansion of world trade in the 17th century (see note 1) and again during the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries. The world may be at the cusp of another global revolution enabled by the Information Age and the technologies and cultures of the Internet. (see note 2) The discipline of SE now has the unique opportunity of providing the tools and methods for the next round of enterprise transformations. Enterprise systems engineering (ESE) is an emerging discipline that focuses on frameworks, tools, and problem-solving approaches for dealing with the inherent complexities of the enterprise. A good overall description of ESE is provided by (Rebovich and White 2011).

- Note 1. “The Dutch East India Company… was a chartered company established in 1602, when the States-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly to carry out colonial activities in Asia. It was the first multinational corporation in the world and the first company to issue stock. It was also arguably the world's first megacorporation, possessing quasi-governmental powers, including the ability to wage war, negotiate treaties, coin money, and establish colonies.” (emphasis added, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_India_Company)

- Note 2. This new revolution is being enabled by cheap and easily usable technology, global availability of information and knowledge, and increased mobility and adaptability of human capital. The enterprise level of analysis is only feasible now because organizations can work together to form enterprises in a much more fluid manner.

6.1.2

Key Terms

Enterprise

An enterprise consists of a purposeful combination (e.g., network) of interdependent resources (e.g., people, processes, organizations, supporting technologies, and funding) that interact with 1) each other (to, e.g., coordinate functions, share information, allocate funding, create workflows, and make decisions), and 2) their environment(s), to achieve (e.g., business and operational) goals through a complex web of interactions distributed across geography and time. (Rebovich and White 2011, pp. 4, 10, 34-35).

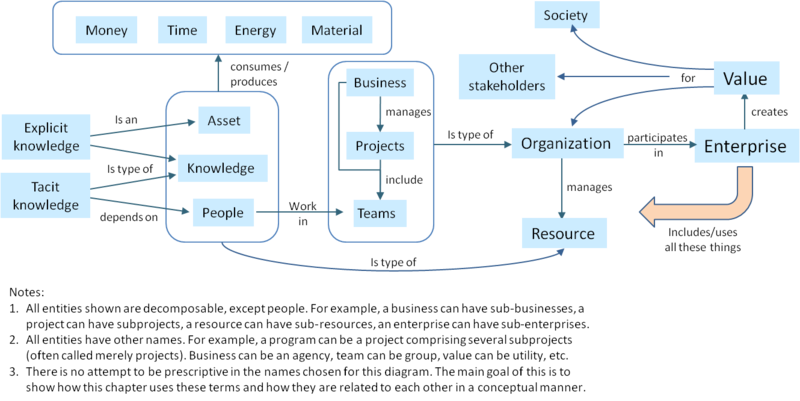

It is worth noting that an enterprise is not equivalent to “organization” according to this definition. This is a frequent misuse of the term enterprise. The figure below shows that multiple organizations participate in an enterprise. (An enterprise that has a single organization participating in it is not likely large enough to warrant the use of ESE practices and principles.)

Enterprise SE

Enterprise Systems Engineering (ESE), for the purpose of this article, is defined as the application of SE (see note 3) principles, concepts, and methods to the planning, design, improvement, and operation of an enterprise. To enable more efficient and effective enterprise transformation, the enterprise needs to be looked at “as a system,” rather than as a collection of functions connected solely by information systems and shared facilities (Rouse 2009). While a systems perspective is required for dealing with the enterprise, this is rarely the task or responsibility of people who call themselves systems engineers.

- Note 3. This form of systems engineering includes 1) those traditional principles, concepts, and methods that work well in an enterprise environment, and 2) an evolving set of newer ideas, precepts, and initiatives derived from complexity theory and the behavior of complex systems (such as those observed in nature and human languages).

6.1.3

Creating Value

The basic concepts that drive the enterprise context of SE are shown in Figure 1. There are three types of organization of interest – businesses, (see note 4) projects, and teams. A typical business participates in multiple enterprises through its portfolio of projects. Large SE projects can be enterprises in their own right, with participation by many different businesses, and may be organized as a number of sub-projects.

- Note 4. The use of the word “business” is not intended to mean only for-profit commercial ventures. As used here it also includes government agencies and not-for-profit organizations, as well as commercial ventures. Business is the activity of providing goods and services involving financial, commercial, and industrial aspects.

Resource Optimization

A key choice for businesses that conduct SE is to what extent, if at all, they seek to optimize their use of resources – people, knowledge, assets – across teams, projects, and business units. (Optimization of resources is not the goal in itself, but rather a means to achieve the goal of maximizing value for the enterprise and its stakeholders.) At one extreme in a product-oriented organization, projects may be responsible for hiring, training, and firing their own staff, and managing all assets required for their delivery of products or services.

At the other extreme in a functional organization, the projects delegate almost all their work to functional groups. In between these two extremes is a matrix organization that is used to give functional specialists a “home” between project assignments. A full discussion of organizational approaches and situations along with their applicability in enabling SE for the organization is provided in Chapter 7.

Note: Red text in this figure is to indicate changes from the version of this diagram in SEBOK draft v0.25.

Figure 1. Organizations Manage Resources to Create Enterprise Value (Figure Developed for BKCASE)

Enabling SE in the Organization

SE skills, techniques, and resources are relevant to many enterprise functions, and a well-founded SE capability can make a substantial contribution at the enterprise level as well as the project level. Chapter 7 discusses enabling SE in the organization, while Chapter 6 focuses on the cross-organizational functions at the enterprise level. <<Add reference to chapter on Architecture>> <<Add reference to SOS chapter>>

Kinds of Knowledge Used by the Enterprise

Knowledge is a key resource for SE. There are generally two kinds of knowledge, explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge can be written down or incorporated in computer codes. Much of the relevant knowledge, however, is “tacit knowledge” that only exists within the heads of people and in the context of relationships that people form with each other (e.g., team, project, and business level knowledge). The ability of an organization to create value is critically dependent on the people it employed, on what they know, how they work together, and how well they are organized and motivated to contribute to the organization’s purpose.

6.1.4

Projects, Programs & Businesses

The term “program” is used in various ways in different domains. In some domains a team can be called a program (e.g., customer support team is their customer relationship "program"), in others an entire business is called a program (e.g., wireless communications business unit program), and in others the whole enterprise is called a program (e.g., the Joint Strike Fighter program). And in many cases the terms project and program are used interchangeably with no discernible distinction in their meaning or scope. Typically, but not always, there are Program Managers who have profit and loss (P&L) responsibility and are the ultimate program decision makers. A Program Manager may have a portfolio of items (services, products, facilities, intellectual property, etc.) that are usually provided, implemented, or acquired through projects.

6.1.5

Practical Considerations

When it comes to performing SE at the enterprise level there are several good practices to keep in mind (Rebovich and White 2011):

- Set enterprise fitness as the key measure of system success. Leverage game theory and ecology, along with the practices of satisfying and governing the commons.

- Deal with uncertainty and conflict in the enterprise though adaptation: variety, selection, exploration, and experimentation.

- Leverage the practice of layered architectures with loose couplers and the theory of order and chaos in networks.

Enterprise governance involves shaping the political, operational, economic, and technical (POET) landscape. One shouldn't try to control the enterprise like one would in a TSE effort at the project level.

6.1.6

Overview of the ESE Knowledge Area

This series of articles will first provide (1) some background on the scope of ESE, imperatives for enterprise transformation, and potential SE enablers for the enterprise. It will then discuss (2) how ESE relates to system of systems (SoS) and a federation of systems (FoS). Next it will describe (3) related business activities and necessary extensions of TSE that enable (4) ESE activities. Each of the ESE process activities is discussed (5) in the overall context of the unique circumstances in the operation of a large and complex enterprise. Finally, it will show (6) how ESE can be used to establish and maintain enterprise operational capabilities. These six Topics are listed below.

6.1.7

Primary References

There are a few publications that serve as key references for the emerging discipline of ESE:

- Rebovich, G., and B. E. White, eds. 2011. Enterprise systems engineering: Advances in the theory and practice. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press.

- Rouse, W. B. 2005. A theory of enterprise information. Systems Engineering, the Journal of the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) 8 (4): 279-95.

- Nightingale, D, and R. Valerdi, eds. 2011. Journal of Enterprise Transformation. Taylor & Francis.

- Sage, A. P., and W. B. Rouse, eds. 2009. Handbook of system engineering and management. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- White, B. E. 2008. Complex adaptive systems engineering (CASE). Paper presented at Understanding Complex Systems Symposium, 12-15 May 2008, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign.

- Bernus, P., N. Laszlo, and G. Schmidt, eds. 2003. Handbook on enterprise architecture, eds. L. Nemes, G. Schmidt. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

NOTE: These key references need to have an overview description added for each one.

Citations in this Article

<<Citations to be listed here>>

6.1.8

Additional References and Readings

Full list of references to be added here.

Topics

The topics contained within this knowledge area include:

- Enterprise Systems Engineering Background

- The Enterprise as a System

- Related Business Management Activities

- Enterprise Systems Engineering Key Concepts

- Enterprise Systems Engineering Process Activities

- Enterprise Capability Management

Article Discussion

Dick F. posting:

Should equal attention be given to services (along with products and enterprises)?