Difference between revisions of "Enterprise Systems Engineering Process Activities"

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

6.6.1 | 6.6.1 | ||

| − | ==References== | + | ==References== |

| − | + | Please make sure all references are listed alphabetically and are formatted according to the Chicago Manual of Style (15th ed). See the [http://www.bkcase.org/fileadmin/bkcase/files/Wiki_Files__for_linking_/BKCASE_Reference_Guidance.pdf BKCASE Reference Guidance] for additional information. | |

| + | ===Citations=== | ||

| + | List all references cited in the article. Note: SEBoK 0.5 uses Chicago Manual of Style (15th ed). See the [http://www.bkcase.org/fileadmin/bkcase/files/Wiki_Files__for_linking_/BKCASE_Reference_Guidance.pdf BKCASE Reference Guidance] for additional information. | ||

| + | ===Primary References=== | ||

| + | All primary references should be listed in alphabetical order. Remember to identify primary references by creating an internal link using the ‘’’reference title only’’’ ([[title]]). Please do not include version numbers in the links. | ||

| + | ===Additional References=== | ||

| + | All additional references should be listed in alphabetical order. | ||

====Article Discussion==== | ====Article Discussion==== | ||

Revision as of 17:26, 24 June 2011

6.6 ESE Process Activities (3.1.5) 6.6.1

SE Role in Transforming the Enterprise

Enabling Systematic Enterprise Change

The SE process as applied to the enterprise as a whole could be used as the “means for producing change in the enterprise … [where the] … Seven Levels of change in an organization [are defined] as effectiveness, efficiency, improving, cutting, copying, differentiating and achieving the impossible.” (McCaughin and DeRosa 2006). Ackoff tells us that:

Data, information, knowledge and understanding enable us to increase efficiency, not effectiveness. The value of the objective pursued is not relevant in determining efficiency, but it is relevant in determining effectiveness. Effectiveness is evaluated efficiency. It is efficiency multiplied by value. [Intelligence] is the [ability to increase efficiency]; [wisdom] is the [ability to increase effectiveness].

The difference between efficiency and effectiveness is reflected in the difference between development and growth. Growth does not require an increase in value; development does. Therefore, development requires an increase in [wisdom as well as understanding, knowledge and information]. ((Ackoff 1989, 3-9), emphasis added)

Effectiveness vs. Efficiency

The essential nature of ESE is that it “determines the balance between complexity and order and in turn the balance between effectiveness and efficiency. When viewed as the fundamental mechanism for change, it goes beyond efficiency and drives adaptation of the enterprise.” (McCaughin and DeRosa 2006) They provide a reasonably good definition for an enterprise that captures well this notion of balance:

Enterprise: People, processes and technology interacting with other people, processes and technology, serving some combination of their own objectives, those of their individual organizations and those of the enterprise as a whole.

Enterprise Management Process Areas

The “System and Program Management” process area is dropped from the matrix since, in an enterprise, this process area is not directly applicable. Instead, this is the responsibility of the Programs within the Enterprise. This process area is replaced with the following four process areas (which, altogether, are the key elements of the Enterprise Management process that oversees the “SE” of the enterprise as a whole):

- Strategic Technical Planning

- Capability-Based Planning Analysis

- Technology and Standards Planning

- Enterprise Evaluation and Assessment

6.6.2

Strategic Technical Planning

The purpose of strategic technical planning is to establish the overall technical strategy for the enterprise. It creates the balance between the adoption of standards and the use of new technologies, along with consideration of the people aspects driven by the relevant transdisciplinary technical principles and practices from psychology, sociology, organizational change management, etc. This process uses the roadmaps developed during technology and standards planning. It then maps these technologies and standards against the capabilities road¬map to determine potential alignment and synergy. Furthermore, lack of alignment and synergy is identified as a risk to avoid or an opportunity to pursue in the technical strategy. The technical strategy is defined in terms of implementation guidance for the programs and projects.

6.6.3

Capability-Based Planning Analysis

The purpose of capability-based planning analysis is to translate the enterprise vision and goals into a set of current and future capabilities that helps achieve those goals. Current missions are analyzed to determine their suitability in supporting the enterprise goals. Potential future missions are examined to determine how they can help achieve the vision. Current and projected capabilities are assessed to identify capability gaps that prevent the vision and technical strategy from being achieved. These capability gaps are then used to assess program, project, and system opportunities that should be pursued by the enterprise. This is defined in terms of success criteria of what the enterprise is desired to achieve.

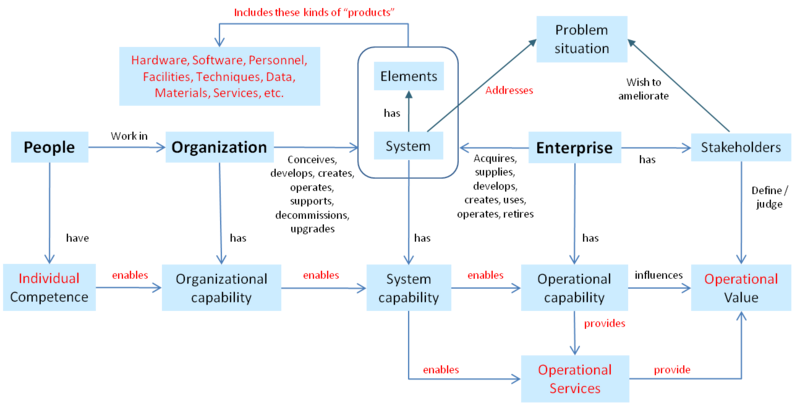

There are different types of capabilities as shown in Figure 20. It is common practice to describe capabilities in the form of capability hierarchies (need REF) and capability roadmaps. Technology roadmaps (discussed below under Technology Planning) are usually related to the system capabilities while business capability roadmaps (BCRMs) are related the operational capabilities of the enterprise as a whole. (ref: Business-Capability Mapping: Staying Ahead of the Joneses, http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb402954.aspx) The BCRM development is usually done as part of Enterprise Strategic Planning, which is one level higher than, and a key driver for, the Strategic Technical Planning activity described above.

In some domains there may be competency roadmaps dealing with the organizational capabilities, with perhaps the desired competency levels of individuals mapped out in terms of the jobs or roles used in the enterprise or perhaps in terms of the knowledge and skills required for certain activities. (REF article on SE competency)

Note: Red text in this figure is to indicate changes from the version of this diagram in SEBOK draft v0.25.

Figure 20. Organizational, System & Operational Capabilities (Figure Developed for BKCASE)

6.6.4

Technology and Standards Planning

The purpose of technology planning is to characterize technology trends in the commercial marketplace and the research community. This activity covers not just trend identification and analysis, but also technology development and transition of technology into programs and projects. It identifies current and predicts future technology readiness levels for the key technologies of interest. Using this information, it defines technology roadmaps. This activity helps establish the technical strategy and implementation guidance in the strategic technical plan. The Business Capabilities Roadmap (BCRM) from the Strategic Planning activity is used to identify which technologies can contribute to achieved targeted levels of performance improvements.

The purpose of standards planning is to assess technical standards to determine how they inhibit or enhance the incorporation of new technologies into systems development projects. The future of key standards is forecast to determine where they are headed and the alignment of these new standards with the life cycles for the systems in the enterprise’s current and projected future portfolios. The needs for new or updated standards are defined and resources are identified that can address these needs. Standardization activities that can support development of new or updated standards are identified.

6.6.5

Enterprise Evaluation and Assessment

The purpose of enterprise evaluation and assessment (EE&A) is to determine if the enterprise is heading in the right direction. It does this by measuring progress towards realizing the enterprise vision. This process helps to “shape the environment” and to select among the program, project, and system opportunities. This is the primary means by which the technical dimensions of the enterprise are integrated into the business decisions.

This process establishes a measurement program as the means for collecting data for use in the evaluation and assessment of the enterprise. These measures help determine whether the strategy and its implementation are working as intended. Measures are projected into the future as the basis for determining discrepancies between what is observed and what had been predicted to occur. This process helps to identify risks and opportunities, diagnose problems, and prescribe appropriate actions. Sensitivity analysis is performed to determine the degree of robustness and agility of the enterprise.

Roberts states that EE&A must go beyond traditional system evaluation and assessment practices. (Roberts 2006) He says that this process area:

must de-emphasize the utility of comparing detailed metrics against specific individual requirement values, whether the metrics are derived from measurement, simulation or estimation… [it] must instead look for break points where capabilities are either significantly enhanced or totally disabled. Key characteristics of this activity are the following:

- Multi-scale analysis

- Early and continuous operational involvement

- Lightweight command and control (C2) capability representations

- Developmental versions available for assessment

- Minimal infrastructure

- Flexible modeling and simulation (M&S), operator-in-the-loop (OITL), and hardware-in-the-loop (HWIL) capabilities

- In-line, continuous performance monitoring and selective forensics. (Roberts 2006)

Enterprise architecture can be used as a primary tool in support of evaluation and assessment. Enterprise architecture can be used to provide a model to understand how the parts of the enterprise fit together (or don’t). (Giachetti 2010) The structure and contents of the enterprise architecture should be driven by the key business decisions (or, as shown in the six-step process in (Martin 2005), the architecture should be driven by the “business questions” to be addressed by the architecture). The evaluation and assessment success measures can be put into the enterprise architecture models and views directly and mapped to the elements that are being measured. An example of this can be seen in the NOAA Enterprise Architecture shown in (Martin 2003a). The measures are shown, in this example, as success factors, key performance indicators, and information needs in the business strategy layer of the architecture.

Enterprise architecture can be viewed as either the set of artifacts developed as “views” of the enterprise, or as a set of activities that create, use and maintain these artifacts. In other words, enterprise architecture can be viewed as either the “noun” (i.e., things) or the “verb” (i.e., actions). The literature uses these terms in both senses and it is not always clear in each case which sense is intended.

6.6.6

Opportunity Assessment and Management

The management activities dealing with opportunities (as opposed to just risk) are included in ESE. According to White (2006), the “greatest enterprise risk may be in not pursuing enterprise opportunities.” Hillson believes there is:

a systemic weakness in risk management as undertaken on most projects. The standard risk process is limited to dealing only with uncertainties that might have negative impact (threats). This means that risk management as currently practiced is failing to address around half of the potential uncertainties—the ones with positive impact (opportunities). (Hillson 2004)

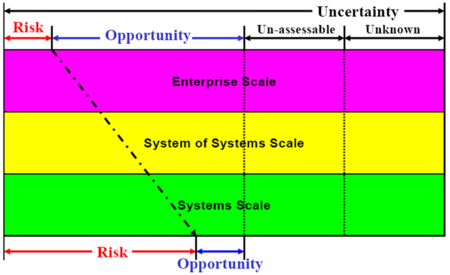

White claims that “in systems engineering at an enterprise scale the focus should be on opportunity, and that enterprise risk should be viewed more as something that threatens the pursuit of enterprise opportunities.” (White 2006) Figure 21 (Rebovich and White 2011, chapter 5) shows the relative importance of opportunity and risk at the different scales of an individual system, a SoS, and an enterprise. The implication is that, at the enterprise level, there should be more focus on opportunity management than on risk management.

Figure 21. Risk and Opportunity at the Enterprise Scale versus the Systems Scale (Source: (Rebovich and White 2011))

6.6.7

Enterprise Architecture and Requirements

Enterprise architecture (EA) goes above and beyond the technical components of product systems to include additional items such as strategic goals and objectives, operators and users, organizations and other stakeholders, funding sources and methods, policies and practices, processes and procedures, facilities and platforms, infrastructure, and real estate. Enterprise architecture can be used to provide a model to understand how the parts of the enterprise fit together (or don’t). (Giachetti 2010) The EA is not strictly the province of the chief information officer (CIO), and is not only concerned with information technology. Likewise, enterprise requirements need to focus on the cross-cutting measures necessary to ensure overall enterprise success. Some of these enterprise requirements will apply to product systems, but they may also apply to business processes, inter-organizational commitments, hiring practices, investment directions, and so on (Bernus, Laszlo, and Schmidt 2003).

Architecture descriptions following the guidelines of an architecture framework have been used to standardize the views and models used in architecting efforts. (Zachman 1987, 276-292; Spewak 1992) Architecture descriptions have also been developed using a business-question based approach. (Martin 2004b; Martin 2006) The ISO/IEC 42010 standard (ISO/IEC 2007) is expanding its scope to include requirements on architecture frameworks.

Government agencies have been increasingly turning to SE to solve some of their agency-level (i.e., enterprise) problems. This has sometimes led to the use of an architecture-based investment process, especially for information technology procurements. This approach imposes a requirement for linking business strategies to the development of enterprise architectures. The Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework (CIO Council 1999) and the DOD Architecture Framework (DODAF) (DoD 2009) were developed to support such an architecture-based investment process. There have been several other architecture frameworks also developed for this purpose. (ISO 2000; ISO/IEC 1998; NATO 2004; MOD 2004; Wikipedia 2010, 1)

6.6.8

ESE Process Elements

As a result of the synthesis outlined above, the ESE process elements to be used at the enterprise scale are as follows:

- Strategic Technical Planning

- Capability-Based Planning Analysis

- Technology and Standards Planning

- Enterprise Evaluation and Assessment

- Opportunity and Risk Assessment and Management

- Enterprise Architecture and Conceptual Design

- Enterprise Requirements Definition and Management

- Program and Project Detailed Design and Implementation

- Program Integration and Interfaces

- Program Validation and Verification

- Portfolio and Program Deployment and Post Deployment

- Portfolio and Program Life Cycle Support

The first seven of these elements were described in some detail above. The others are more self-evident and will not be discussed in this article.

6.6.1

References

Please make sure all references are listed alphabetically and are formatted according to the Chicago Manual of Style (15th ed). See the BKCASE Reference Guidance for additional information.

Citations

List all references cited in the article. Note: SEBoK 0.5 uses Chicago Manual of Style (15th ed). See the BKCASE Reference Guidance for additional information.

Primary References

All primary references should be listed in alphabetical order. Remember to identify primary references by creating an internal link using the ‘’’reference title only’’’ (title). Please do not include version numbers in the links.

Additional References

All additional references should be listed in alphabetical order.