Technical Planning

Systems engineering planning is performed concurrently and collaboratively with project planning. It involves developing and integrating technical plans to achieve the technical project objectives within the resource constraints and risk thresholds. The planning involves the success-critical stakeholders to ensure that necessary tasks are defined with the right timing in the life cycle in order to manage acceptable risks levels, meet schedules, and avoid costly omissions.

SE Planning Process Overview

Systems engineering (SE) planning provides the following elements:

- Definition of the project from a technical perspective,

- Definition or tailoring of engineering processes, practices, methods, and supporting enabling environments to be used to develop products or services, as well as plans for transition and implementation of the products or services, as required by agreements,

- Definition of the technical organizational, personnel, and team functions, and responsibilities, as well as all disciplines required during the project life cycle,

- Input to the definition of the appropriate life cycle model or approach for the products or services,

- Definition and timing of technical reviews, product or service assessments, and control mechanisms across the life cycle, including the success criteria in terms of cost, schedule, and technical performance at identified project milestones,

- Estimation of technical cost and schedule based on the effort needed to meet the requirements; this estimation becomes input to project cost and schedule planning,

- Determination of critical technologies, as well as the associated risks and actions needed to manage and transition these technologies,

- Identification of linkages to other project management efforts, and

- Documentation of and commitment to the technical planning.

Scope

SE planning begins with analyzing the scope of technical work to be performed and understanding the constraints, risks, and objectives that define and bound the solution space for the product or service. The planning includes estimating the size of the work products, establishing a schedule (or integrating the technical tasks into the project schedule), identification of risks, and negotiating commitments. Iteration of these planning tasks may be necessary to establish a balanced plan with respect to cost, schedule, technical performance, and quality. The planning continues to evolve with each life cycle phase of the project (NASA 2007, 1-360; SEI 1995, 12).

SE planning includes all programmatic and technical elements of the project to ensure a comprehensive and integrated plan for all of the project's technical aspects. The SE planning should account for the full scope of technical activities, including system development and definition, risk management, quality management, configuration management, measurement, information management, production, verification and test, integration, validation, and deployment. The SE planning integrates all SE functions to ensure that plans, requirements, operational concepts, and architectures are consistent and feasible.

The scope of the planning can vary, from planning a specific task to developing a major technical plan. The integrated planning effort will determine what level of planning and accompanying documentation is appropriate for the project.

Integration

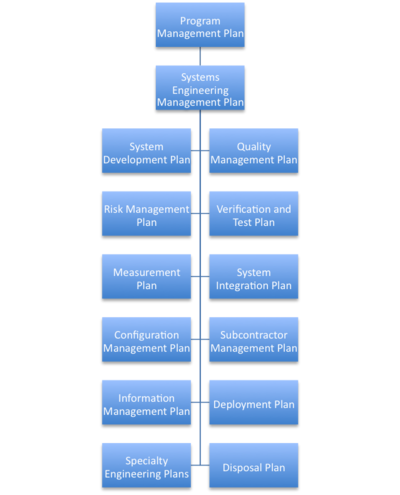

The integration of each plan with other higher level, peer, or subordinate plans is an essential part of SE planning. For the technical effort, the systems engineering management plan (SEMP), also frequently known as the systems engineering plan (SEP), is the highest level technical plan. It is subordinate to the project plan, and often has a number of subordinate technical plans providing detail on specific technical focus areas (INCOSE 2011, sec. 5.1.2.2; NASA 2007, appendix J).

In U.S. defense work, the terms SEP and SEMP are not interchangeable. The SEP is a high level plan made before the system acquisition and development begins. It is written by the government customer. The SEMP is the specific development plan written by the developer (or contractor). The intent and content are quite different. For example, a SEP will have an acquisition plan that would not be included in a SEMP. Figure 1 below shows the SEMP and integrated plans.

More details

Task planning identifies the specific work products, deliverables, and success criteria for systems engineering efforts in support of integrated planning and project objectives. The success criteria are defined in terms of cost, schedule, and technical performance at identified project milestones. Detailed task planning identifies specific resource requirements (e.g., skills, equipment, facilities, and funding) as a function of time and project milestones.

SE planning is accomplished by both the acquirer and supplier, and the activities for SE planning are performed in the context of the respective enterprise. The activities establish and identify relevant policies and procedures for managing and executing the project management and technical effort; identifying the management and technical tasks, their interdependencies, risks, and opportunities; and providing estimates of needed resources/budgets. Plans are updated and refined throughout the development process based on status updates and evolving project requirements (SEI 2007).

Linkages to Other Systems Engineering Management Topics

The project planning process is closely coupled with the measurement, assessment and control, decision management, and risk management processes.

The measurement process provides inputs for estimation models. Estimates and other products from planning are used in decision management. Systems engineering assessment and control processes use Planning results for setting milestones and assessing progress. Risk management uses the planning cost models, schedule estimates, and estimate uncertainty distributions to support quantitative risk analysis (as desired).

Additionally, planning needs to use the outputs from assessment and control and risk management to ensure corrective actions have been accounted for in planning future activities. The planning may need to be updated based on results from technical reviews (from assessment and control), measurement, issues identified during the performance of risk management activities, or decisions made as a result of the decision management activities (INCOSE 2010, sec. 6.1).

Practical Considerations

Pitfalls

Some of the key pitfalls encountered in planning and performing SE planning are listed in Table 1 (Developed for BKCASE) below.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Incomplete and Rushed Planning |

|

| Inexperienced Staff |

|

Good Practices

Some good practices gathered from the references are in Table 2 (Developed for BKCASE) below.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Use Multiple Disciplines |

|

| Early Conflict Resolution |

|

| Task Independence |

|

| Define Interdependencies |

|

| Risk Management |

|

| Management Reserve |

|

| Use Historical Data |

|

| Consider Lead Times |

|

| Update Plans |

|

| Use IPDTs |

|

Additional good practices can be found in the Systems Engineering Guidebook for Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), NASA Systems Engineering Handbook, the INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook, and Systems and Software Engineering - Life Cycle Processes - Project Management (Caltrans and USDOT 2005, 278; NASA December 2007, 1-360, sec. 6.1; INCOSE 2011, sec. 5.1; USAF 2004, Chapter 4; ISO/IEC/IEEE 2009, Clause 6.1).

References

Works Cited

Caltrans, and USDOT. 2005. Systems Engineering Guidebook for Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS). Version 1.1. Sacramento, CA, USA: California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) Division of Reserach & Innovation/U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT), SEG for ITS 1.1.

DAU. 2010. Defense Acquisition Guidebook (DAG). Ft. Belvoir, VA, USA: Defense Acquisition University (DAU)/U.S. Department of Defense, February 19.

INCOSE. 2011. INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities. Version 3.2.1. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.2.1.

ISO/IEC/IEEE. 2009. Systems and Software Engineering - Life Cycle Processes - Project Management. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electronical Commission (IEC)/Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), ISO/IEC/IEEE 16326:2009(E).

NASA. 2007. NASA Systems Engineering Handbook. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NASA/SP-2007-6105.

SEI. 1995. A systems engineering capability maturity model. Version 1.1. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Software Engineering Institute (SEI)/Carnegie-Mellon University (CMU), CMU/SEI-95-MM-003.

Primary References

Caltrans and USDOT. 2005. Systems Engineering Guidebook for Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS). Version 1.1. Sacramento, CA, USA: California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) Division of Reserach & Innovation/U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT), SEG for ITS 1.1.

DAU. 2010. Defense Acquisition Guidebook (DAG). Ft. Belvoir, VA, USA: Defense Acquisition University (DAU)/U.S. Department of Defense.

INCOSE. 2011. INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities. Version 3.2.1. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.2.1.

ISO/IEC. 2008. Systems and Software Engineering - System Life Cycle Processes. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electronical Commission (IEC), ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288:2008 (E).

NASA. 2007. NASA Systems Engineering Handbook. Washington, D.C., USA: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NASA/SP-2007-6105.

SEI. 1995. A Systems Engineering Capability Maturity Model. Version 1.1. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Software Engineering Institute (SEI)/Carnegie-Mellon University (CMU), CMU/SEI-95-MM-003.

SEI. 2007. Capability Maturity Model Integrated (CMMI) for Development. Version 1.2, measurement and analysis process area. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Software Engineering Institute (SEI)/Carnegie Mellon University (CMU).

Additional References

Boehm, B et al. 2000. Software Cost Estimation with COCOMO I. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall

DeMarco, T and Lister, T. 2003. Waltzing with Bears; Managing Risks on Software Projects. New York, NY, USA: Dorset House.

Valerdi, R. 2008. The Constructive Systems Engineering Cost Model (COSYSMO): Quantifying the Costs of Systems Engineering Effort in Complex Systems. Saarbrücken,Germany: VDM Verlag Dr. Muller

ISO/IEC/IEEE. 2009. Systems and Software Engineering - Life Cycle Processes - Project Management Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electronical Commission (IEC)/Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), ISO/IEC/IEEE 16326:2009(E).

Comments from SEBok 0.5 Wiki

No comments were logged for this article in the SEBoK 0.5 wiki. Because of this, it is especially important for reviewers to provide feedback on this article. Please see the discussion prompts below.

SEBoK Discussion

Please provide your comments and feedback on the SEBoK below. You will need to log in to DISQUS using an existing account (e.g. Yahoo, Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) or create a DISQUS account. Simply type your comment in the text field below and DISQUS will guide you through the login or registration steps. Feedback will be archived and used for future updates to the SEBoK. If you provided a comment that is no longer listed, that comment has been adjudicated. You can view adjudication for comments submitted prior to SEBoK v. 1.0 at SEBoK Review and Adjudication. Later comments are addressed and changes are summarized in the Letter from the Editor and Acknowledgements and Release History.

If you would like to provide edits on this article, recommend new content, or make comments on the SEBoK as a whole, please see the SEBoK Sandbox.

blog comments powered by Disqus