System Realization

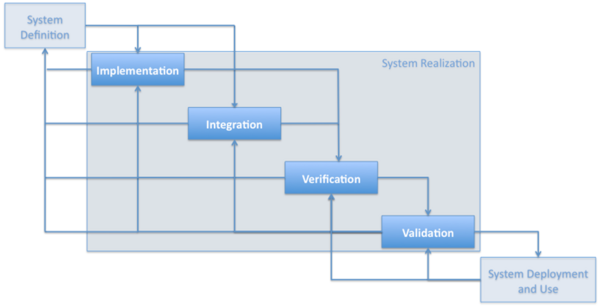

<html> <meta name="citation_title" content="System Realization"> <meta name="citation_author" content="Pyster, Art"> <meta name="citation_author" content="Olwell, David H."> <meta name="citation_author" content="Hutchison, Nicole"> <meta name="citation_author" content="Enck, Stephanie"> <meta name="citation_author" content="Anthony, James F., Jr."> <meta name="citation_author" content="Henry, Devanandham"> <meta name="citation_author" content="Squires, Alice (eds)"> <meta name="citation_publication_date" content="2012/11/30"> <meta name="citation_journal_title" content="Guide to the Systems Engineering Body of Knowledge (SEBoK)"> <meta name="citation_volume" content="version 1.0.1"> <meta name="citation_pdf_url" content="http://www.sebokwiki.org/1.0.1/index.php?title=Main_Page"></html> This knowledge area (KA) will discuss the system realization stage in a traditional life cycle process. This includes those processes required to build a system (system implementation), integrate disparate system elements (system integration), and ensure that the system both meets the needs of stakeholders (system validation) and aligns with the system requirements and architecture (System Verification). These processes are not sequential; their iteration and flow are depicted in Figure 1 (see "Overview", below), which also shows how these processes fit within the context of system definition and System Deployment and Use KAs.

Topics

Each part of the SEBoK is divided into KAs, which are groupings of information with a related theme. The KAs in turn are divided into topics. This KA contains the following topics:

See the article Matrix of Implementation Examples for a mapping of case studies and vignettes included in Part 7 to topics covered in Part 3.

Overview

Essentially, the outputs of system definition are used during system implementation to create system elements and during system integration to provide plans and criteria for combining these elements. The requirements are used to verify and validate system elements, systems, and the overall system-of-interest (SoI). These activities provide feedback into the system design, particularly when problems or challenges are identified.

Finally, when the system is considered verified and validated, it will then become an input to system deployment and use. It is important to understand that there is overlap in these activities; they do not have to occur in sequence as demonstrated in Figure 1. Every life cycle model includes realization activities, in particular verification and validation activities. The way these activities are performed is dependent upon the life cycle model in use. (For additional information on life cycles, see the Life Cycle Models KA.)

The realization processes are performed to ensure that the system will be ready to transition and has the appropriate structure and behavior to enable desired operation and functionality throughout the system’s life span. Both DAU and NASA include transition in realization in addition to implementation, integration, verification, and validation (Prosnik 2010; NASA December 2007, 1-360).

Fundamentals

Macro View of Realization Processes

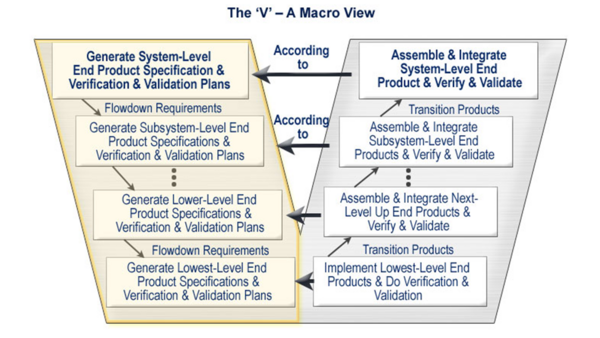

Figure 2 illustrates a macro view of generic outputs from realization activities when using a Vee life cycle model. The left side of the Vee represents various design activities 'going down' the system.

The left side of the Vee model demonstrates the development of system elements specifications and design descriptions. In this stage, verification and validation plans are developed which are later used to determine whether realized system elements (products, services, or enterprises) are compliant with specifications and stakeholder requirements. Also, during this stage initial specifications become flow-down requirements for lower-level system models. In terms of time frame, these activities are going on early in the system’s life cycle. These activities are discussed in the System Definition KA. However, it is important to understand that some of the system realization activities are initiated at the same time as some system definition activities; it is in particular the case with integration, verification and validation (IV&V) planning.

The right side of the Vee model, as illustrated in Figure 2, results in system elements that are assembled into products, services, or enterprises according to the system model described during the left side of the Vee (Integration). Verification and validation activities determine how well the realized system fulfills the stakeholder requirements, the system requirements, and design properties. These activities should follow the plans developed on the left side of the Vee. Integration can be done continuously, incrementally and/or iteratively, supported by verification and validation (V&V) efforts. For example, integration typically starts at the bottom of the Vee and continues upwards to the top of the Vee.

The U.S. Defense Acquisition University (DAU) provides this overview of what occurs during system realization:

Once the products of all system models have been fully defined, Bottom-Up End Product Realization can be initiated. This begins by applying the Implementation Process to buy, build, code or reuse end products. These implemented end products are verified against their design descriptions and specifications, validated against Stakeholder Requirements and then transitioned to the next higher system model for integration. End products from the Integration Process are successively integrated upward, verified and validated, transitioned to the next acquisition phase or transitioned ultimately as the End Product to the user. (Prosnik 2010)

While the systems engineering (SE) technical processes are life cycle processes, the processes are concurrent, and the emphasis of the respective processes depends on the phase and maturity of the design. Figure 3 portrays (from left to right) a notional emphasis of the respective processes throughout the systems acquisition life cycle from the perspective of the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). It is important to note that from this perspective, these processes do not follow a linear progression. Instead, they are concurrent, with the amount of activity in a given area changing over the system’s life cycle. The red boxes indicate the topics that will be discussed as part of realization.

References

Works Cited

DAU. 2010. Defense Acquisition Guidebook (DAG). Ft. Belvoir, VA, USA: Defense Acquisition University (DAU)/U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). February 19, 2010.

Prosnik, G. 2010. Materials from "Systems 101: Fundamentals of Systems Engineering Planning, Research, Development, and Engineering". DAU distance learning program. eds. J. Snoderly, B. Zimmerman. Ft. Belvoir, VA, USA: Defense Acquisition University (DAU)/U.S. Department of Defense (DoD).

Primary References

INCOSE. 2011. INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities. Version 3.2.1. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.2.1.

ISO/IEC/IEEE. 2008. Systems and Software Engineering - System Life Cycle Processes. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electronical Commission (IEC), Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288:2008 (E).

Martin, J.N. 1997. Systems Engineering Guidebook: A process for developing systems and products. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press.

NASA. 2007. Systems Engineering Handbook. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NASA/SP-2007-6105.

Additional References

DAU. 2010. Defense Acquisition Guidebook (DAG). Ft. Belvoir, VA, USA: Defense Acquisition University (DAU)/U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). February 19, 2010.

DAU. Your Acquisition Policy and Discretionary Best Practices Guide. In Defense Acquisition University (DAU)/U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) [database online]. Ft Belvoir, VA, USA. Available at: https://dag.dau.mil/Pages/Default.aspx (accessed 2010).

ECSS. 2009. Systems Engineering General Requirements. Noordwijk, Netherlands: Requirements and Standards Division, European Cooperation for Space Standardization (ECSS), 6 March 2009. ECSS-E-ST-10C.

IEEE. 2012. "Standard for System and Software Verification and Validation". Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. IEEE 1012.

SEBoK Discussion

Please provide your comments and feedback on the SEBoK below. You will need to log in to DISQUS using an existing account (e.g. Yahoo, Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) or create a DISQUS account. Simply type your comment in the text field below and DISQUS will guide you through the login or registration steps. Feedback will be archived and used for future updates to the SEBoK. If you provided a comment that is no longer listed, that comment has been adjudicated. You can view adjudication for comments submitted prior to SEBoK v. 1.0 at SEBoK Review and Adjudication. Later comments are addressed and changes are summarized in the Letter from the Editor and Acknowledgements and Release History.

If you would like to provide edits on this article, recommend new content, or make comments on the SEBoK as a whole, please see the SEBoK Sandbox.

blog comments powered by Disqus