Generic Life Cycle Model

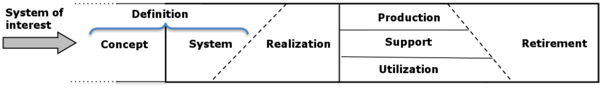

As discussed in the generic life cycle paradigm in Introduction to Life Cycle Processes each system-of-interest has an associated life cycle model . The generic life cycle model below applies to a single SoI. SE must generally be synchronised across a number of such life cycle models to fully satisfy stakeholder needs. More complex life cycle models which address this are described in Life Cycle Models.

A Generic System Life Cycle Model

There is no single “one-size-fits-all” system life cycle model that can provide specific guidance for all project situations. Figure 1, adapted from (Lawson 2010, ISO/IEC 2008, and ISO/IEC 2010), provides a generic life cycle model that forms a starting point for the most common versions of pre-specified, evolutionary, sequential, opportunistic, and concurrent life cycle processes. The model is defined as a set of stages, within which technical and management activities are performed. The stages are terminated by decision gates where the key stakeholders decide whether to proceed into the next stage, to remain in the current stage, or to terminate or re-scope related projects.

Elaborated definitions of these stages are provided below, in the glossary, and in various other ways in subsequent articles.

The Concept Definition stage begins with a decision by a protagonist (individual or organization) to invest resources in a new or improved system. Inception begins with a set of stakeholders agreeing to the need for a system and exploring whether a new or modified system can be developed, in which the life cycle benefits are worth the investments in the life cycle costs. Activities include: developing the concept of operations and business case; determining the key stakeholders and their desired capabilities; negotiating the stakeholder requirements among the key stakeholders and selecting the system’s non-developmental items (NDIs).

The System Definition stage begins when the key stakeholders decide that the business needs and stakeholder requirements are sufficiently well defined to justify committing the resources necessary to define a whole system solution in sufficient detail to answer the life cycle cost questions identified in concept definition and provide a basis of system realization if appropriate. Activities include developing the system’s architecture; defining and agreeing levels of system requirements; developing systems-level life cycle plans and performing system analysis in order to illustrate the compatibility and feasibility of the resulting system definition. The transition into the system realization stage can lead to either single-pass or multiple-pass development.

It should be noted that the concept and system definition activities above describe activities performed by systems engineers when performing systems engineering. There is a very strong concurrency between proposing a problem situation or opportunity and describing one or more possible system solutions, as discussed in Systems Approach Applied to Engineered Systems. Other related definition activities include: prototyping or actual development of high-risk items to show evidence of system feasibility; collaboration with business analysts or performing mission effectiveness analyses to provide a viable business case for proceeding into realization; and modifications to realized systems to improve their production, support or utilization. These activities will generally happen through the system life cycle to handle system evolution, especially under multiple-pass development. This is discussed in more detail in the Life Cycle Models knowledge area.

The System Realization stage begins when the key stakeholders decide that the system elements and feasibility evidence are sufficiently low-risk to justify committing the resources necessary to develop and sustain the initial operational capability (IOC) or the single-pass development of the full operational capability (FOC). Activities include: construction of the developmental elements; integration of these with each other and with the non-developmental item (NDI) elements; verification and validation (V&V) of the elements and their integration as it proceeds; and preparing for the concurrent production, support, and utilization activities.

The System Production, Support, and Utilization (PSU) stages begins when the key stakeholders decide that the system life-cycle feasibility and safety illustrate a sufficiently low-risk level that justifies committing the resources necessary to produce, field, support, and utilize the system over its expected lifetime. The lifetimes of production, support, and utilization are likely to be different. Aftermarket support will generally continue after production is complete and users will often continue to use unsupported systems.

System Production involves the fabrication of system copies or versions and of associated aftermarket spare parts. It also includes production quality monitoring and improvement; product or service acceptance activities; and continuous production process improvement. It may include low-rate initial production (LRIP) to mature the production process or to promote the continued preservation of the production capability for future spikes in demand.

Systems Support includes various classes of maintenance: corrective (for defects), adaptive (for interoperability with independently evolving co-dependent systems), and perfective (for enhancement of performance, usability, or other key performance parameters). It also includes hot lines and responders for user or emergency support and the provisioning of needed consumables (gas, water, power, etc.). Its boundaries include some gray areas, such as the boundary between small system enhancements and the development of larger complementary new additions, and the boundary between rework/maintenance of earlier fielded increments in incremental or evolutionary development. Systems Support usually continues after System Production is terminated.

System Utilization includes the use of the system by operators, administrators, the general public, or systems above it in the system-of-interest hierarchy. It usually continues after Systems Support is terminated.

The System Retirement stage is often executed incrementally as system versions or elements become obsolete or are no longer economical to support and therefore undergo disposal or recycling of their content. Increasingly affordable considerations make system re-purposing an attractive alternative.

Life Cycle Process Terminology

Requirement

A requirement is something that is needed or wanted, but may not be compulsory in all circumstances. Requirements may refer to product or process characteristics or constraints. Different understandings of requirements are dependent on process state, level of abstraction, and type (e.g. functional, performance, constraint). An individual requirement may also have multiple interpretations over time.

Requirements exist at multiple levels of enterprise or system with multiple levels af bstraction. This ranges from the highest level of the enterprise capability or customer need to the lowest level of the system design .Thus, requirements need to be defined at the appropriate level of detail for the level of the entity to which it applies. See the article Transforming Enterprise Need to Requirements for further detail on the transformation of needs and requirements from the enterprise to the lowest system element across concept definition and system definition.

Architecture

An architecture refers to the organizational structure of a system, whereby the system can be defined in different contexts. Architecting is the art or practice of designing the structures. See the article Iterative and Recursive System Definition for further discussion on the use of levels of Logical and Physical architecture to define related system and system elements; and support the requirements activities.

Architectures can apply for a system, product, enterprise, or service. For example, Part 3 mostly considers product-related architectures that systems engineers create, but enterprise architecture describes the structure of an organization. Part 5: Enabling Systems Engineering interprets enterprise architecture in a much broader manner than an IT system used across an organization, which is a specific instance of architecture.

Frameworks are closely related to architectures, as they are ways of representing architectures. The terms Architecture Framework and Architectural Framework both refer to the same. Examples include: DoDAF, MoDAF, NAF for representing systems in defense applications, the TOGAF open group Architecture Framework, and the Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework (FEAF) for information technology acquisition, use and disposal. See the glossary of terms Architecture Framework for definition and other examples.

Other Processes

A number of other life cycle processes are mentioned above, including system analysis , integration , verification , validation , deployment, operation, maintenance and disposal are discussed in detail in the System Realization and System Deployment and Use knowledge areas.

Life Cycle Process Sequence

In the above description we have listed key activities critical to successful completion of each stage. This is a useful way to illustrate the goals of each stage and gives an indication of how processes align with these stages. This can be important when considering how to plan for resources, milestones, etc. However, it is important to observe that the execution of process activities are not compartmentalized to particular life cycle stages (Lawson 2010).

Figure 2 show a simple illustration of the through life nature of technical an management processes. This figure builds directly on the "hump diagram" principles described in Systems Approach Applied to Engineered Systems.

insert figure here

The lines on this diagram represent the amount of activity for each process over the generic life cycle. The peaks (or humps) of activity represent the periods when a process activity becomes the main focus of a stage. The activity before and after these peaks may represent through life issues raised by a process focus, e.g. how will likely maintenance constraints be represented in the system requirements, these considerations help maintain a more holistic perspective in each stage. Or they can represent forward planning to ensure the resources needed to complete future activities have been included in estimates and plans, e.g. are all resources need for verification in place or available. Ensuring this hump diagram principle is implemented in a way which is achievable, affordable and appropriate to the situation is a critical driver for all life cycle models.

Figure 1 shows just the single-step approach for proceeding through the stages of a system’s life cycle. In Life Cycle Models knowledge area we discuss examples of real world enterprises and their drivers, both technical and organizational. These have lead to a number of documented approaches for sequencing the life cycle stages to deal with some of the issues raised. The Life Cycle Models KA summarizes a number of incremental and evolutionary life cycle models, including their main strengths and weaknesses and also discusses criteria for choosing the best-fit approach.

References

Works Cited

ISO/IEC/IEEE. 2015.Systems and software engineering - system life cycle processes.Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.ISO/IEC 15288:2015.

Lawson, H. 2010. A Journey Through the Systems Landscape. London, UK: College Publications.

Primary References

Blanchard, B.S., and W.J. Fabrycky. 2011. Systems Engineering and Analysis, 5th ed. Prentice-Hall International series in Industrial and Systems Engineering. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall.

Forsberg, K., H. Mooz, H. Cotterman. 2005. Visualizing Project Management, 3rd Ed. Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons.

INCOSE. 2012. Systems Engineering Handbook, version 3.2.2. San Diego, CA, USA: International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE). INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.2.2.

Lawson, H. 2010. A Journey Through the Systems Landscape. London, UK: College Publications.

Pew, R. and A. Mavor (eds.). 2007. Human-System Integration in The System Development Process: A New Look. Washington, DC, USA: The National Academies Press.

Additional References

Chrissis, M., M. Konrad, and S. Shrum. 2003. CMMI: Guidelines for Process Integration and Product Improvement. New York, NY, USA: Addison Wesley.

Larman , C. and B. Vodde. 2009. Scaling Lean and Agile Development. New York, NY, USA: Addison Wesley.

SEBoK Discussion

Please provide your comments and feedback on the SEBoK below. You will need to log in to DISQUS using an existing account (e.g. Yahoo, Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) or create a DISQUS account. Simply type your comment in the text field below and DISQUS will guide you through the login or registration steps. Feedback will be archived and used for future updates to the SEBoK. If you provided a comment that is no longer listed, that comment has been adjudicated. You can view adjudication for comments submitted prior to SEBoK v. 1.0 at SEBoK Review and Adjudication. Later comments are addressed and changes are summarized in the Letter from the Editor and Acknowledgements and Release History.

If you would like to provide edits on this article, recommend new content, or make comments on the SEBoK as a whole, please see the SEBoK Sandbox.

blog comments powered by Disqus